If you’ve not read Parts 1 and 2 of A Guide for Translators, start here:

Introduction

This series, A Guide for Translators, explores some of the ambiguities hiding within the term “phenomenal consciousness”, one of two default labels for the central explanatory target in discussions of consciousness. The definitional issues are impossible to separate from the greater challenge of understanding consciousness, and I think the entire process is being thwarted by continued use of this term.

I’ll be using the phrase “phenomenal consciousness” a lot, so I’ll write it as “PC”; the abbreviation carries no specific connotations compared to the long form.

“Qualia”, a partial synonym, is the other main option. It’s also a messy term worthy of dissection, but it does not map cleanly to consciousness itself, and it’s potentially subject to even more confusion, so I’ll leave it aside for now.

In Part 1 of this series, (On a Confusion about Phenomenal Consciousness), I introduced Austin and Delilah, two hypothetical physicalists. They were both virtualists, seeing phenomenal properties in representational terms, but, for the purposes of the story, they could have been more conventional physicalists.

Despite having similar concepts of reality, they argued all night about the ontological status of PC. Austin used “PC” to mean ostensional consciousness (a set of phenomena picked out by introspection) and Delilah used the same term to mean phenomenal spice (an entity imagined to differentiate humans from zombies).

In Part 2 (The Spice-Meal Conflation), I introduced Harry and Sally, two hardists who applied the same mismatched definitional mappings that had led Austin and Delilah to argue. Harry and Sally failed to notice their conflicting definitions, because their concept of PC stretched across both versions. They were indifferent to whether PC was identified on ostension or imagined as missing in a zombie — and indeed this indifference is required for belief in the possibility of zombies. To suppose that zombies are possible is to suppose that a single concept of PC can cover both roles: giving us our understanding of what zombies are supposed to be missing, while also referring to something that dances above the causal story, not shifting any of our concepts from their physically determined path, and not adding content to anything we think or say, including what we think and say about zombies.

I referred to this confusion as the Spice-Meal Conflation, because it is similar to the ambiguity that affects the English word “curry”; we often apply the same word to a range of spicy Asian meals and to the spices within those meals. Curry-the-meal = bland stuff + curry-the-spice.

For consciousness, the situation can be summarised as: the phenomenal properties found on introspection (Σ) consist of bland functional stuff (ρ) and a disputed phenomenal extra (Δ).

Note that this linguistic analogy is hardist-friendly, because in the culinary case the add-on is real, and it really does carry most of the flavour. The anti-hardist counterargument is left making the claim that the bland stuff of neuroscience, unseasoned with any mysterious extras, is already flavourful enough. In the non-culinary version, the spice is fictional or irrelevant, and its reputation for phenomenal flavour actually relies on a hybrid concept that includes the previously underappreciated bland elements. This is the conceptual hybrid (ρ/Δ) actually driving hardism. The Spice-Meal Conflation relies, in part, on not seeing both elements of this hybrid.

Ostensional consciousness (Σ) =

functional elements accessed introspectively (ρ) +

phenomenal spice (Δ).

In this post and the next (Part 3 of the series is broken into two sections for posting), I’ll be arguing that Block’s original use of his term was so riddled with contradictions that it was destined for trouble from the start, and I’ll be discussing a “new” PC conflation — it’s thirty years old, but it’s new to this blog, and I’ve not seen it discussed elsewhere.

In addition to the falling into the traps already considered (the Spice-Meal Conflation, Δ/Σ, and the unacknowledged hybrid, ρ/Δ) , Block’s paper applies the term “phenomenal consciousness” to two different axes of meaning, without seeming to notice that he has done so. One axis relates to a subjective-objective divide applied to individual brain-states, and it is the natural focus of hardist puzzlement, the other to a distinction applied between brain-states. Confusingly, Block uses the concept of “phenomenal consciousness” to mark conceptual positions on either axis.

I’ll call this the Biaxial Conflation. It is closely related to the conflations already considered, but raises a whole new set of issues.

The first of the two axes is the familiar one at the centre of hardism: the physical sciences give us one conception of what brain states are like, and subjective experience provides us with something else. This is the axis that Mary’s knowledge seems to move along when she is released; it is the dimension along which we notionally separate humans and zombies. Everyone has a different opinion on whether this distinction should be conceptualised in epistemic or ontological terms. I think it is most usefully seen as a conceptual dualism related to different handling of substrate and content.

In suggesting “phenomenal consciousness” as a label for subjective states, Block’s 1995 paper seemingly labelled one end of this familiar axis. In doing so, he created the conditions for the term to be adopted by hardists as the preferred name for their explanatory target, which is itself built on conflations.

The very next year, when Chalmers published “The Conscious Mind” in 1996, he treated “PC” as a synonym for his “experience”, the entity that supposedly defied explanation and justified the positing of new ontologies.

A number of alternative terms and phrases pick out approximately the same class of phenomena as “consciousness” in its central sense. These include “experience,” “qualia,” “phenomenology,” “phenomenal,” “subjective experience,” and “what it is like.” Apart from grammatical differences, the differences among these terms are mostly subtle matters of connotation. “To be conscious” in this sense is roughly synonymous with “to have qualia,” “to have subjective experience,” and so on. Any differences in the class of phenomena picked out are insignificant.

[…]

In what follows, I revert to using “consciousness” to refer to phenomenal consciousness alone. When I wish to use the psychological notions, I will speak of “psychological consciousness” or “awareness.” It is phenomenal consciousness with which I will mostly be concerned.

(Chalmers, 1996, The Conscious Mind. Emphasis added.)

Even though this adoption departed substantially from Block’s usage, as will be discussed in this post and the next, it is not surprising. Block’s paper included sections that directly map to all of the key hardist themes: the total resistance of PC to any analytic definition, the lack of (overt) functionality in PC, the idea that PC stands outside cognition, the association of PC with the Explanatory Gap, and — most important of all — the explicit identification of phenomenal consciousness as the thing zombies lack.

All of this is evidence that Block was probably in the grip of the same hardist intuitions that stand behind the Hard Problem, which was introduced in Chalmers’ landmark “Facing Up” paper in 1995, the same year that gave us “phenomenal consciousness”.

The situation is not that clear, though.

In some parts of Block’s paper, he appears to accept the full scope of the Hard Problem (though not by that name), including its strong, zombie-focussed and weak, gap-focussed forms (which, you guessed it, are often conflated, as discussed elsewhere). On the other hand, Block had, by that time, published a paper arguing against epiphenomenal conceptions of consciousness, and his 1995 paper was primarily concerned with the second axis of potential meaning for “PC”, the neurobiological distinction between states. Block was clearly ambivalent about many of the hardist intuitions, and parts of his paper can even be seen as putting up a token resistance to hardism, trying to steer the debate towards a biological conception of phenomenality.

The second axis of meaning in Block’s Bi-Axial cluster concept relates to Block’s attempt to separate “phenomenal consciousness” from a more functional conception of consciousness, which he called “access consciousness”. He attempted to illustrate the utility of this distinction, by picking out paradigmatic P-states and A-states. Since then, his neurobiological notion of a P/A distinction has received much less attention than the hardist focus on the subjective-objective divide.

The conflation between these two axes is much less subtle than the tricky issues underlying hardism. Once it has been pointed out, this second axis is quite easy to see, and it involves empirical matters that would show up on an appropriate brain scan. It’s important to discuss, though, because it adds to the difficulty of extracting a clean meaning for “PC” and identifying it as “the one Block intended”.

This conflation is also inspired by (and demonstrates) some of the same confusion that manifests as hardism, so it casts light on the other conflations. All of these issues are hopelessly intertwined, and even identifying two axes adds a coherence that was not there in the original paper.

This second axis is essentially concerned with neurobiological matters relevant to whether a state should be considered “phenomenal”. As such, it is orthogonal to the conflations already considered in this series, and the confusion across these two axes would continue to be problematic if spice-related ideas had never surfaced.

Block appears to have been trying to find a neurobiological basis for the conceptual dualism of the subjective-objective divide, which is an important step that any successful theory of consciousness must achieve. His paper directly appeals to the Explanatory Gap and to what he thinks are physical correlates of the Gap, so Block was trying to do something that I am predisposed to think is a good idea: naturalise the Gap and explain it in neurobiological terms.

Unfortunately, I think his paper fails in that attempt, and it leaves us with a conceptual mess, instead — not just because it left “PC” ripe for adoption by hardists and committed many of the conflations central to hardism, but because Block also conflated two orthogonal axes that should have been kept conceptually separate.

His phenomenal-access division tried to be at least two different things at once.

All physicalists must ultimately argue that the subjective-objective conceptual divide driving hardism arises from physical reality (because everything arises from physical reality, including our understanding or misunderstanding of it). It is therefore important to see where Block goes wrong, and to note where similar ideas, with minor tweaks, can be salvaged within a new framework with cleaner terminology.

To anticipate, I think Block was looking in the wrong brain for the answer.

In a later post (Part 4 of this series), I’ll consider Chalmers’ adoption of Block’s term and the overall hardist approach to PC.

Chalmers was quick to accept “PC” as a synonym for his elusive non-functional “experience”, but, in doing so, he dropped one entire semantic axis and substantially changed its meaning. Whereas Block had tried to tie “PC” to specific aspects of mentality that were amenable to illustrative anecdotes and potentially related to distinct neurobiological processes, Chalmers instead focussed on a single axis. He drew a line between: 1) anything we might be able to characterise in objective neurobiological terms; and 2) some elusive extra we can only feel.

Chalmers is not entirely to blame for this shift in meaning. The conceptual seeds of the profound Chalmersian division were already there in Block’s paper, because Block wrote of subjective “phenomenal consciousness” and objective “access consciousness”, which seemed to map to Chalmers’ two ontological dimensions, and Block also talked of zombies, which provide paradigmatic illustrations of the primary hardist divide between physical functions and phenomenal feels. Chalmers’s appropriation of the term could even be seen as imposing a metaphysical neatness on what was initially a messy set of contradictory ideas hovering around a central introspective concept. Unfortunately, his use of Block’s terminology created the impression that there were two distinct consciousness systems and that the Hard Problem was appropriately directed at one of them. The Hardness was not just in the heads of those trying to puzzle their way through the issues; it was there in the generic subject, with its own official name.

Regardless of whether we think this was a good move, much of Block’s original concept of PC was jettisoned. The idea of phenomenal spice, which was initially at the fringes of Block’s cluster of concepts, ended up promoted to a position of importance — under the still overloaded label of “phenomenal consciousness”. (Despite the removal of several meanings, the Spice-Meal Conflation and the ρ/Δ hybrid were still key parts of the surviving concept.)

In a later post (Part 5), I’ll consider a laudable attempt by Eric Schwitzgebel to reign in all this confusion. He proposes that we can rehabilitate “phenomenal consciousness” by taking an innocent, theory-neutral approach; we can achieve a definition by compiling a list of positive exemplars, free of any theoretical commitments, and considering their commonalities. I don’t think this is possible, but, if we were determined to keep the term, this might be our best option.

In the end, though, I think the existing confusion associated with the term is so great that this approach will necessarily fail: we need a new term for this potentially cleaner concept, and clear guidelines for use. Otherwise, all the potential conflations will remain in play. Pointing within a representational system is never entirely innocent; it comes with distinct hazards.

In a final post (Part 6), I’ll consider the conflations of hardism and Block’s biaxial conception via a two-brain approach, which will also give us a new way of talking about pseudo-irreducibility and pseudo-epiphenomenalism, two key elements of the Meta-Problem of Consciousness.

The three philosophers considered in Parts 3, 4 and 5 of this series all take a very different approach to phenomenal consciousness, and they end up in very different places, but they are all inspired by the same starting point: we introspect, and we find some aspect of mentality that seems to have non-functional flavours. We find colours and pains and experiential awareness, all of which seem difficult to derive from physical facts and easy to imagine as absent in a purely physical ontology.

In all three cases, the key conceptual conflations discussed in my previous posts remain relevant. In places, those conflations appear directly within the published work of the relevant philosopher, but sometimes the conceptual slippage occurs in the author’s unacknowledged background assumptions, or in our own intuitive reactions to their work. To some extent, this is inevitable. Even a faultless account of the way things actually are, delivered by an omniscient God, would have to be taken on by a human mind predisposed to hardist bafflement. To be frank, I think Block’s original paper took a contradictory, scattergun approach that set us up for confusion. Chalmers takes a much more consistent line, at least linguistically: he always treats “PC” as a non-functional extra and thereby largely avoids overt contradictions — but I think his entire framing relies on unacknowledged conceptual conflations behind the scenes. Schwitzgebel takes a definitional stance that would work well enough if everyone complied, but I think we need specific measures and a new name to safeguard his target concept from the hardist intuitions that everyone inevitably brings to his “innocent” list.

All of these definitional issues are resolvable, but my central claim in this series is that the term “phenomenal consciousness” is not fit for purpose; it is not even suitable for rehabilitation. It straddles too many incompatible concepts; it is applicable to too many distinct ontological entities (and non-entities). It encourages and disguises an insidious drift between incompatible ideas that need their own, distinct names. I think continued use of this term will inevitably perpetuate the confusion for which the consciousness debate is famous, and we should abandon it.

In saying this, I don’t just mean that the term “phenomenal consciousness” is built on a faulty understanding of the world, in the way that élan vital turned out to be a bad idea. We need terms for bad ideas, in order to discuss them and to distinguish them from the alternatives. Moreover, I actually think “PC” can be aligned with good ideas, and Schwitzgebel is on the right track. There is something in reality that this term picks out (perhaps indirectly), something that is genuinely puzzling and needs to be discussed, and no suitable replacement term has widespread currency.

If only we could ban all the other uses of the term, we’d be fine.

“Phenomenal consciousness” is not really analogous to “élan vital”, which referred to a clear concept resting on faulty assumptions. It is more like a hypothetical mongrel term that the vitalist debate never had to contend with: something like “life vitality”, used by some authors to refer to a fictitious animating spirit, by others to the real phenomenon of life, and by others to a hybrid that confuses the debate so badly that the rejection of élan vital could be mistaken for the denial of life.

What, you mean we’re all dead? That’s the silliest claim ever made.

The real problem is that “PC” encompasses elements of the debate that are fundamentally incompatible with each other. Sometimes those incompatible ideas are caught up in the same thought experiment, and often they are hybridised into a single muddled concept. For instance, we need a cognitively accessible, contentful version of PC to perform the essentially cognitive act of imagining zombies while telling ourselves that the imagined differences are non-cognitive. This is easy if we are dealing with a hybrid concept, but the exercise starts to look incoherent if we pull the hybrid apart and name the components. The spice concept plays a key role, but it can’t get any content from its purported target.

If the consciousness debate were poised slightly differently, we could argue about the true nature of “PC” while using it as a vague umbrella term for all the different possibilities of what it might turn out to be, acknowledging that many of the possibilities being considered are mutually incompatible. A charitable interpretation of Block’s paper suggests that he was attempting just that. Here is a central phenomenon that needs explaining, he was saying, and here are several ways it might map to reality. Perhaps distinct neurobiological processes are involved, perhaps it is all a matter of conceptual perspective; maybe phenomenality is a distinct property that could go missing in a perfect functional or physical mimic.

Unfortunately, his division of consciousness into “phenomenal consciousness” and “access consciousness” strongly suggested that we have two distinct forms of consciousness, not just two different conceptual views of consciousness, and this goes well beyond theory-neutral recognition of a phenomenon seen from a particular perspective and acknowledged as such. The proposed division was applied unevenly and inconsistently across the complex, multi-layered puzzle that consists of scientists and philosophers attempting to use their own modular cognition to understand the modular cognition of a generic subject brain.

In the process, Block gave hardists a new way of characterising all functional accounts of the brain as missing the target of primary interest. Chalmers, in the same year, was arguing that functional accounts of cognition address the Easy Problems of consciousness, but fail to address the Hard Problem. Block appeared to be saying something very similar: functional accounts only explain access consciousness; they leave out phenomenal consciousness.

Indeed, I have heard this exact line expressed by modern hardists. It is a form of Chalmers’ Razor (the topic of a forthcoming post), which can be defined as the rejection of any proposed functional account of phenomenal consciousness on the grounds that it can be imagined in bland, functional terms that leave out phenomenality.

The contradictions in this 30-year old paper are worth discussing, not just because this is where the current terminological issues started, but because all of these contradictory concepts are still available, and still in use. Right from the start, there has never been a single meaning for “phenomenal consciousness”; the term came from a place of confusion. Block introspected and found puzzling mental phenomena, and he wanted to distinguish them from objectively tractable features of brain activity that were also called consciousness. Beyond this, he does not seem to have had a consistent framework. Block’s biaxial cluster of possible meanings distracts from the major conflations that were already to be found in Chalmers’ much simpler notion of “experience”, making it even harder to identify the more subtle sources of confusion. Each of Block’s disparate usages is still a potential target for what we’re all trying to understand, each of them offering yet another potential anchor point for a confused term.

Indeed, the biaxial confusion that started with Block continues to this day.

Philosophers often adopt the hardist interpretation along the perspectival axis. Scientists are still writing papers about phenomenal consciousness under the false impression that it has some neurobiological meaning that is coherent enough to study — as though there were a distinct mechanism to match the name Block gave to what might only be a point of view. These papers are immediately rejected by hardists because anything describable in a scientific paper cannot possibly be what they have in mind; all mechanisms can be imagined a missing phenomenality. Something stranger is needed to bridge the Gap.

This analysis of Block’s paper will be highly critical, but it has a constructive aspect, as well. It is important to consider the Biaxial Conflation and the interplay between axes because some of the cognitive modularity that Block was trying to identify with his discussion of “phenomenal” states and “access” states is important, not for the reasons he identified, but because that same modularity plays a major role in the Meta-Problem of Consciousness. Many of the ideas in his paper can be seen as a near-miss.

If we assign his contradictory ideas to two different brains in a two-brain approach, thinking about what makes a state a phenomenal state or an access state in terms of the cognitive modularity of the on-looking scientist, rather than in the generic brain under study, many of the contradictions become comprehensible. Where Block’s Biaxial Conflation unwittingly merges 1) different perspectives applied to single brain-states with 2) a separation of brain-states, a two-brain approach explicitly involves different cognitive states in the notional Scientist being applied to a single brain-state in the notional Subject. The many-to-one cognitive relationship creates the entire hardist puzzle. Many of the same conceptual tensions are present, in this view, but they can all be understood.

Two Dimensions of Phenomenal-Access Distinction

This post and the next will be structured around the two major dimensions in Block’s Biaxial Conflation. In this post (Part 3A) the Biaxial Conflation will be explained, and in the next (Part 3B), Block’s paper will be assessed for evidence that he truly supported each axis, despite the contradictions.

One of these dimensions, the perspectival or hardist dimension, involves the conflation discussed in the previous post, The Spice-Meal Conflation, which lies at the centre of hardism. Adding the second, neurobiological dimension creates a new conflation I’ve not previously discussed, apart from a few brief comments above.

Ironically, Block justified the need for the term “phenomenal consciousness” by suggesting that two different conceptions of consciousness were being conflated by other authors. He proposed that we use the expression “phenomenal consciousness” (“P-consciousness”) for the subjective phenomena of consciousness, and he contrasted this with a more functional, objective conception of consciousness, which he called “access consciousness” (A-consciousness).

Other authors, he suggested, were setting out to explain mysterious aspects of consciousness but settling for a functional account of something much more mundane, the behaviourally salient aspects of awareness. Chalmers lodged a very similar complaint with his “Facing Up” paper. It is understandable that some people have interpreted the two authors as saying much the same thing, and I believe their parallel complaints come from the same intuitive source.

In his opening paragraphs, Block indicated that the term “phenomenal consciousness” should cover the subjective phenomena picked out on introspection, the ones that stand in need of explanation.

This is what I’ve called ostensional consciousness.

Let me acknowledge at the outset that I cannot define P‑consciousness in any remotely non‑circular way. I don’t consider this an embarrassment. The history of reductive explanations in philosophy should lead one not to expect a reductive explanation of anything. But the best one can do for P‑consciousness is in some respects worse than for many other things because really all one can do is point to the phenomenon… P‑conscious states are experiential states… We have P‑conscious states when we see, hear, smell, taste and have pains. (Block, 1995)

He defined “access consciousness” in terms that were more closely related to behaviour, including cognitive states with an obvious potential link to behaviour, such as explicit reasoning.

“A state is access conscious (A‑conscious) if, in virtue of one’s having the state, a representation of its content is (1) inferentially promiscuous, that is, poised for use as a premise in reasoning, (2) poised for rational control of action, and (3) poised for rational control of speech. . . These three conditions are together sufficient, but not all necessary.” (Block, 1995)

To clarify the phenomenal-access distinction, Block wrote:

The paradigm P‑conscious states are sensations, whereas the paradigm A‑conscious states are "propositional attitude" states such as thoughts, beliefs, and desires, states with representational content expressed by "that" clauses (e. g., the thought that grass is green.)

This makes intuitive sense. Sensations like seeing green with its distinctive flavour expose the puzzle of subjective consciousness in its most vivid form — that’s what the whole qualia debate is about. Those are the phenomena behind Colin McGinn’s pithy prequel to the Hard Problem: “How can technicolour phenomenology arise from soggy grey matter?” Conversely, we can readily envisage mechanisms that let soggy grey matter hold an item of information ready for use as a premise in reasoning, or poised for behavioural manifestation in action or speech. We’ve already created machines that can manipulate propositions and apply primitive reasoning (though many people continue to debate whether those propositions can mean anything without some connection to mental phenomenology).

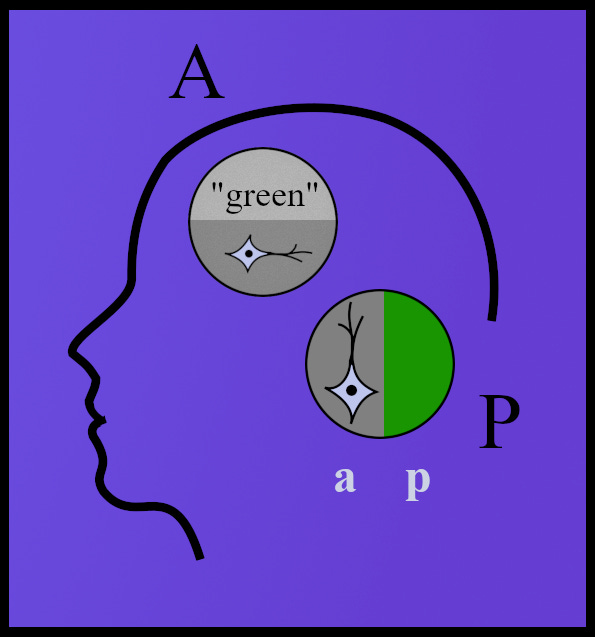

Unfortunately, even in these early paragraphs, Block is alluding to two different conceptions of what it means to be phenomenal — despite the fact that spice-related issues have not yet made their appearance, we already have a conflation. His examples (sensations vs propositions) are tweaking two variables at once: the content of concepts in different brain-states (colour versus sentences), and the perspective adopted to that content for individual brain-sates (first-person versus third-person).

His P/A distinction therefore moves away from the puzzle of the greenness quale along two dimensions simultaneously, and he is not specifying which dimension is the one of major importance.

Does the phenomenal-access distinction apply horizontally or vertically in the example below?

Superficially, because sensory perceptions with their attendant qualia issues are on one side of Block’s P/A distinction and objective states are on the other, Block’s division corresponds with Chalmers’ separation of consciousness into a set of Easy Problems about the brain’s objective cognitive functions and a Hard Problem about subjective experience. It is no real surprise, then, that Block’s terms were taken up by hardists. Block facilitated this interpretation by referring to PC as non-functional, and by relating PC to zombies and to the Explanatory Gap. We can, if we want, use “access consciousness” to refer to any aspect of mentality that might count as the target of an Easy Problem and reserve “phenomenal consciousness” for the target (or source) of the elusive Hard Problem.

I have encountered many online hardists who do just that.

But that was not Block’s primary intent. He seemed to have in mind a different P/A division, applied between states.

Whereas hardists would place all of the brain’s physical processes in a domain that can be explained in functional terms, and then argue that phenomenality involves some additional flavour not yet accounted for, as in Jackson’s tale of Mary, Block appears to believe that some cerebral processes are innately phenomenal, and others are innately functional. He talks of P-states and A-states, not p- and a-aspects of individual states.

This is entirely different to Chalmers’ approach, though both authors were clearly inspired by the puzzling phenomenal aspects of sensory experiences. (They both started in the top-left of the 2x2 table above).

Armed with all the physical facts and a mature Blockian theory, we could, it is implied, separate different neurobiological processes into P-processes and A-processes. If they were relatively stable over time, we might refer to P-states and A-states, as Block does in his paper. If they were transient, we might refer to P-stages and A-stages of processing, an approach that Block endorsed years later (though he continued to allude to hardist themes as well).

“Phenomenal consciousness is what I really mean by “consciousness”; it's the what‑it's ‑likeness of experience, the redness of red as Kristoff Koch likes to say. Access consciousness is what we do with that phenomenal consciousness when we put it into our cognitive system, when we apply concepts to it and think and reason using the contents of perception.” (Block on YouTube, emphasis added.)

Whether we consider the P/A distinction in spatial or temporal terms, this is an axis of separation that could potentially be described in a text of cognitive neuropsychology (provided we dispensed with the qualia-related issues such as “the redness of red”). This distinction incorporates much of the everyday localisation challenge that a neurologist faces in working out the regional basis of anomalous brain function.

Indeed, it is the sort of separation that is routinely discussed in neuroradiology meetings, with no sense of any philosophical mystery. Clinicians report on whether the patient’s problem was seeing flashes of green in one visual field (a P-state) or in recalling or saying the word “green” (an A-state), and the neuroradiologist guides interpretation of the patient’s MRI scans with that distinction as a major arbiter of what is clinically relevant. In the first case, which is a classic description of a focal epileptic seizure in primary visual cortex, the neuroradiologist might look for a subtle lesion in the grey matter of the corresponding occipital lobe. In the second case, attention would be drawn to the left frontal or temporal lobe, depending on the precise nature of the language difficulty. Loss of the semantic knowledge that grass is green would constitute yet another type of deficit (distinct from specific difficulty with the words) , potentially leading to a dementia workup.

Applying a Chalmersian perspective, we could then note that the P-processes in the occipital lobes, the ones that cause or constitute the experience of greenness, are subject to an Explanatory Gap, and we could ask questions that have no place in any clinical meeting. What is this strange greenness that the patient is seeing? How is it produced by their occipital lobe seizures? Is it even produced? If a patient relates a story of an epileptic hallucination of a green shape, is anything in the reported events truly green? What aspect of reality contains the greenness, both in this special case and in the perfectly ordinary perception of green grass? Is anything in reality actually green in the way our brains seem to portray it? And we all have our different answers, which are heavily disputed, and in most cases nothing empirical is being debated.

These sorts of questions create a second perspectival axis of distinction, indicated in the diagram below using a lower-case p/a terminology, in contrast to the much more tractable neurobiological P/A axis shown in upper-case.

The anatomy is deliberately simplified, but the occipital lobe activity is shown as a split circle, half in green. The neural activity that physicalists imagine to be the true ontological substrate of the phenomenal state is depicted as a lone representative neuron, and the greenness being represented is depicted as literally green. This is not, of course, meant to imply that anything in the head is actually green, but the green pixels in the diagram are expected to activate your V4 colour cortex, when you look at the diagram, and so the colour in the diagram might well match what you tend to think the phenomenal state is “like”.

That greenness is not really there, but it is what would show up on a likograph for many people as they thought about this brain-state.

Mary’s difficulty in getting her own occipital V4 neurons to represent greenness by reading about such neurons, without the help of any green pixels, is a large part of what creates intrigue about the p/a axis. This intrigue has nothing directly to do with the fact that other brain-states lack these philosophical challenges, and can be separated from the puzzling perceptual states along Block’s neurobiological P/A axis.

The analogous neuron-word gap for the brain-state involved in representing a proposition is shown in the upper circle, which is similarly split to show content and substrate. Explaining the nature and function of these paradigmatic A-states is relatively straightforward, part of Chalmers’ “Easy” Problems, and close to being solved. Understanding the mechanisms behind transmission of the perceptual greenness information along the P/A axis (from the occipital lobe to the language centres) is also an Easy Problem — and it is something that could literally be interrupted with a surgeon’s blade. A patient’s seizure might even travel along such a path, leading to speech arrest a few seconds after the onset of a flashing hallucination of greenness.

Block’s P-states, such as the one involved in the phenomenal experience of greenness, attract philosophical interest because of the p/a Explanatory Gap, not the P/A anatomical gap. (But the neuroanatomy of the wannabe explainer is involved, a separate matter for a later post.)

There is an apparent dichotomy between what science says P-states consist of (neurons) and what they seem like to the cognitive system contemplating them (green). They have bland objective features (a-type features) and then (if we accept this framing) they can be imagined as having an inexplicable layer of phenomenal flavour (p-type features).

Block lists these states as paradigmatic phenomenal states not because anyone was confusing colour perception with language along the P/A axis, but because he and everyone else is interested in the elusive p-features of P-states. The a-features of P-states and the p-features of A-states are not nearly as challenging to think about. And the a-features of A-states are generally considered to be primarily scientific puzzles, not philosophical mysteries; they are the sort of thing that will be solved at the interface between AI and cognitive neuroscience.

In the 2x2 matrix shown above, only the pP combination raises genuine puzzlement, particularly when trying to relate it to the corresponding aP element, which constitutes an objective view of the same physical brain region.

The A-states also have a content-substrate dichotomy, and pA elements must be related to aA elements, even though this relationship is not one we routinely feel puzzled about.

This is not to say that there is nothing of interest in the right-hand side of the above diagram. The phenomenality of language is not its core feature, but it is worthy of study and far from straightforward. For spoken language, for instance, we seem to add imaginary pauses between words. We also ignore distinctions in vowels and consonants that our semantic centres have been trained to treat as noise, magnifying other distinctions that would be considered much less salient on semantically neutral auditory grounds. We don’t hear semantically neutral noises in human speech, and then interpret it; our experience is always modified by higher-order processes. We don’t get the sense, though, that there is an important Explanatory Gap here (except perhaps when it comes to the generation of meaning, a fraught topic with its own advocates for special biological extras that might be epiphenomenal).

Propositional attitudes have their own philosophical challenges, of course, and the philosophy of language constitutes an entire complex discipline, but the cerebral A-processes involved in language processing or propositional reasoning are largely (not completely) immune to the famous Chalmersian p/a dichotomy and his Hard Problem.

If Linguistic Mary has never seen any colour word but has full access to all the physical facts, the spelling and pronunciation of the word “green” are in the bag. (If she knows the words “greed” and “seen”, the phenomenal aspects of the word are also readily available, and she would probably be able to use the word in her own internal speech as soon as she decoded the neural activity in her textbook, never having been exposed to the word.)

The uppercase P/A and lowercase p/a axes of separation are orthogonal to each other, but they are not entirely independent, because the physical P-states are the ones with the more florid Gap for first-person p-features. Block sets us up for confusion by considering changes along both of these axes within his paper and by using the same term, “phenomenal consciousness”, for what separates A-states from P-states within the brain’s activities and for the two available perspectives on individual P-states, subjective and objective.

Even worse, he takes two different approaches to the p/a axis. He gives credence to the hardist notion that the difference might have a distinct ontological footprint not captured in a perfect physical duplicate (Chalmers’ view), while also briefly acknowledging that this difference in perspective might turn out to be primarily conceptual (my own view).

If we follow Block’s lead, we end up with three broadly different conceptions of the biaxial phenomenal-access distinction: one for the neurobiological conception of distinct P- and A- states, and two different views of the p/a distinction for individual states, one that is primarily ontological and another that is primarily conceptual.

The hardist’s ontological interpretation of the p/a difference, complete with irreducible qualia, shown in the middle of the diagram above.

The primary P/A neurobiological distinction, shown on the far right .

A conceptual p/a distinction that imperfectly but instructively maps back to the initial P/A distinction, because both distinctions reflect similar cognitive modularity.

I’ll consider the first two of these interpretations in the next post (Part 3, continued) , while the conceptual delta in the brain of an on-looking scientist will get its own post.

I will end this post with a brief summary of these three views.

Primarily for the mnemonic value, I tend to associate each of these conceptions with an individual philosopher who has championed a similar perspective, though many other philosophers have said similar things (and Block’s paper entertains all three concurrently, with varying levels of enthusiasm).

David Chalmers argues for an ontological interpretation of the p/a distinction with immaterial qualia. In this view, the Explanatory Gap provides direct ontological insight into the fact that qualia are not directly part of the physical processes involved. This is a distinction applied to individual brain-states within the notional Subject, but it necessarily reflects contrasting, different brain-states within Chalmers (and anyone who adopts a similar view, even momentarily).

Ned Block, as we’ve seen, tries to differentiate between neurobiological P-states and A-states. Although this separation occurs along the P/A axis, it reflects issues that are intimately related to the hardist p/a distinction. Block does not express things this way, but I would say that his neurobiological P/A separation reflects both axes concurrently, because the P/A distinction between states is dominated by the degree to which different aspects of mentality and different cognitive activities are subject to an Explanatory Gap across the p/a divide.

Where our analytic, scientific concepts of a mental state in the Subject and our own use of that state as on-looking Scientists share similar cognitive modules (or allow for analytic translation between concepts and modules), he considers these to be A-states. Where we try and fail to conjure perceptual features through functional analysis of the relevant substrate, but we can reach the concepts through private ostension, we experience frustration. We encounter a barrier to Jacksonian derivation. Block considers these Gap-affected states (and their elusive properties) to be phenomenal. Ostending to a private example is a cognitive tactic we primarily employ for perceptual concepts, at least during introspective contemplation, so paradigmatic P-states are sensations. The apparent exclusion of their introspectively available properties from the scientifically tractable story with its closed causal loops means that it would not take much conceptual slippage to interpret the p-features of these P-states as epiphenomenal, as well.

(There are motor equivalents, such as golf swings, that we activate in toto in a form that largely defies functional analysis, but these motor equivalents of qualia have received much less philosophical attention.)

David Papineau has famously argued for conceptual dualism as the true source of what I have called the hardists’ p/a distinction; this dualism would also account for the most puzzling aspects of Block’s P-states, and it arises from the cognitive modularity he considers along the P/A axis, so it casts light on both of Block’s axes.

Papineau argues that most of the confusion in relation to consciousness stems from our use of quotational, phenomenal concepts, leading to conceptual dualism as shown on the far left of the diagram above. When we think of a P-state in a generic subject, such as the state of seeing green, we activate many of the corresponding neurons in our own heads, and we hold up a representation of greenness as an example of what a representation of greenness is like. (I think many people slip into the phenomenological fallacy at this point, imagining that the state is green in some way.) We also entertain material concepts of phenomenal states, and we find those functional accounts bland compared to our more typical quotational approach. The resulting contrast gives rise to a marked intuition of distinctness, rendered more powerful because we also strongly suspect that there is no available cognitive journey that connects material concepts to phenomenal concepts along an analytical path.

This view (which I think is mostly correct) can also be expressed via a two-brain approach.

The Explanatory Gap primarily represents epistemic difficulties translating between different concepts within the brain of a Scientist, and Chalmers’ ontological interpretation as this indicating a miracle in the Subject is a wild extrapolation from one brain to another.

In this way, much of the same cognitive modularity that Block identified in the Subject along a P/A neurobiological axis turns out to explain the hardist intuition of distinctness along a p/a perspectival axis.

As he says:

…perhaps P‑consciousness and A‑consciousness amount to much the same thing empirically even though they differ conceptually… Perhaps the two are so intertwined that there is no empirical sense to the idea of one without the other.

The Hard Problem of explaining how soggy grey matter generates qualia in the Subject ends up being echoed in the Meta-Problem of explaining why a Scientist would think this way, and both of Block’s axes turn out to be relevant after all, and intimately related.

The duality that causes all the problems would literally show up in a brain scan, as long as it was the Scientist, not the Subject, that we scanned.

Continued in Part 3B…

If you’re finding this series interesting, please support my work and let other readers know by hitting the “Like” button or restacking.