“Is it a problem for your definition of phenomenal consciousness if zombies agree with it?”

Author and Substacker Pete Mandik asked this question in a recent post. (He also added robots into the mix, an aspect of the discussion I won’t touch here.)

This happens to be an issue I’d already thought about — my blog is named after one aspect of this problem — and it turns out that my answer is superficially different to Mandik’s. (He says yes, it is a problem if zombies agree with your definition; I say no, it’s not.)

The divergence in our answers is potentially interesting — for me at least — because I think Mandik and I have a similar ontological outlook, and we both think zombies are impossible.

So let me turn the question around.

Forget that there is such a thing as a human world; the zombies are on their own, now, fending for themselves. What could your zombie twin say about what it calls ‘consciousness’ that would be logically defensible? Lock that answer in.

What valid grounds could you ever have for saying anything other than that?

In what follows, I will assume you know what a philosophical zombie is supposed to be — if you don’t, check out the Wikipedia entry or, for a longer introduction to the idea, read my previous sympathetic exploration of zombies: Your Twin. For a general discussion of the relevance of zombies to this blog, you could start with my introductory post, The Zombie’s Delusion.

I will also assume you are familiar with the concept of phenomenal spice, which is the experiential extra imagined as present in humans but missing in zombies. If not, check out: On a Confusion about Phenomenal Consciousness. That’s a good place to start if you’re new to this blog, but not new to this debate.

Impossible Concepts

Impossible concepts can be quite corrosive to theoretical frameworks, so we should handle them with care, but occasionally they’re benign and sometimes they’re even useful.

Suppose that a maths student at a top tier university is visited by God in a dream, and God tells him that pi is rational: it can be expressed as the ratio of two very large integers.

This revelation comes as a great shock, and it threatens to undermine everything the student has ever believed, but the dream is utterly convincing, and God doesn’t seem likely to be in error.

The next morning, the student goes to his professor, distraught, ready to quit studying maths.

If pi is rational, nothing he’s been taught can be trusted any more.

The professor, let us suppose, is wise, and she has seen this sort of thing before. She asks her student to explore the consequences of pi’s rationality. He’s very bright, so she expects him to rediscover one of the standard proofs that pi must be irrational. Some of these proofs work by exposing a contradiction: start by assuming pi is rational, apply accepted mathematical principles, and yield a blatant, uncontroversial contradiction. The natural conclusion is that the original assumption must have been false.

The student follows this general sequence, but he discovers a new proof of pi’s irrationality, and he gets a published paper out of it.

His trust in divine revelation takes a beating, though, and he vows not to accept cookies from his friend Harry ever again.

Note that the student could have taken a different tack when he attempted his proof-by-contradiction. He could have continued to insist on pi’s rationality, and, in the face of increasing conflict with other parts of maths, he could have concluded that those mathematical principles must be wrong, too, and thereby let all of maths come tumbling down.

He didn’t take this option because distrusting the revelatory dream was more parsimonious than ditching all of maths. It is a matter of weighing up the costs of different approaches. Should he conceptually flip pi back to its original irrational status, which only requires disbelieving a dubious claim encountered in a dream? Or should he let maths itself fail?

What the student learns from this experience is that contradictions can be tolerated in small doses, they are often instructive, and they can often reveal insights into the true cost of keeping the troublesome element in its erroneous state.

Some contradictions are more corrosive than others, though. It might have been a different matter if God had told him 0=1, and a different matter again if God had merely suggested that, maybe, if you’re careful, you actually can take the square root of a negative number and carry on with everything else intact.

The ability to handle challenges of this nature is a sign of a robust conceptual framework. Maths, seen as a body of accepted practices, often has enough inherent consistency to reject a single contradiction, as long as that contradiction can be contained and its unwelcome consequences can be exposed.

Consider the famous Liar Paradox, sometimes attributed to Epimenides via the expression “All Cretans are liars” (written by a Cretan).

This paradox is now usually known in a more direct form: “This sentence is false”.

If it is true then it is false; if false, then true. So which is it?

I can’t tell you the most acceptable way to resolve this paradox in 2025, but it seems likely that, if we don’t want to go crazy thinking about the Liar Paradox, we will need to take a deflationary attitude to the truth values of sets of words. Truth values cannot be as consistent as we might have hoped. There is no grand adjudicator. Sentences don’t ascend to truth clouds or descend to fiery pits of falsehood. Words just sit there, and we read them. Often sentences have stable meanings when we consider them, and sometimes they map usefully to the world, but not always.

Suppose that the very best deflationary semantic system for handling this sort of contradictory sentence is known as D, and that we have very good reasons for thinking D is true.

Consider this sentence that tries to take down D: “The truth value of this sentence is opposite to the truth value of D.”

We can neatly avoid paradox if D is false, because the sentence can settle on a stable truth value: D is false and the sentence is true; they have opposite truth values, just as claimed. All is well.

If D is true, though, the sentence is effectively announcing its own falsity, and we are back to the Liar’s Paradox, the very thing we had hoped to avoid by inventing D.

So D must be false?

No, of course not. If D is as good a theory as we supposed, it is still true, and D, sitting implicitly within a facile sentence that reduces it to a single letter, disarms the very idea that tries to threaten it — the idea that isolated self-referential sentences must be strictly true or false. D would not be a very robust theory of meaning if it let itself be destroyed so easily. It is more parsimonious to keep D and to reject this paradoxical sentence, using the more nuanced understanding expressed within D.

Complex paradigms cannot be brought down by the simple trick of embedding them within a facile paradox.

So it is, I propose, with physicalism and zombies. Physicalism can’t be brought down just because physical brains can conceive of the falsity of physicalism — because hardists can render the truth of physicalism paradoxical in a contrived scenario. It is technically true that physicalism would be falsified by zombies if they were truly logically possible, but if they’re not possible (because, for instance, physicalism is true), we can safely invite them over to play, and we will be all the wiser for their visit.

Your Zombie Twin

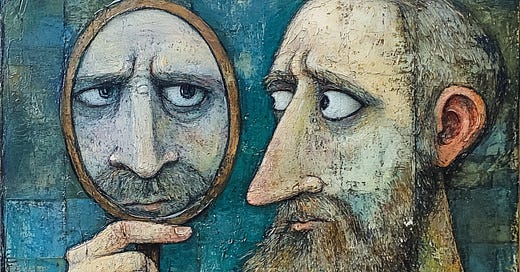

Lately, I’ve spent more time than is probably healthy thinking about my zombie twin. I tend to think about him, not because I believe he is logically possible, but because I think he serves as a useful foil against folly. I even named my blog after his kind.

Now, it has to be conceded that this is conceptually risky. I’m a physicalist, and zombies are incompatible with physicalism. For a zombie to exist, I would have to be wrong about pretty much everything I believe.

But that was also true of the temporarily assumed rationality of pi and the temporarily tolerated anti-D sentence. If we let one falsehood override other important principles, things fall apart, but if we entertain the idea cautiously, we will simply reinforce our confidence that the tentatively entertained falsehood is indeed false.

There are at least three different ways we could approach the potential clash between zombies and definitions of consciousness.

Let’s start with the approach that gives zombies the most scope for causing trouble.

We could reason that zombies lack consciousness, so, if zombies share our definition of consciousness, that proves our definition can be deployed in error, by beings who lack consciousness; our definition doesn’t pin down consciousness well enough to distinguish between a zombie’s spurious use of the definition and a human’s justified use.

Suppose, for instance, that a zombie says, “I think, therefore I’m not a zombie”, and it bases its definition of consciousness on its conviction that it has some special Cartesian insight into its own consciousness. It’s obviously wrong, but how can we capture the special human element that makes a human expression of this special conviction superior to a zombie’s unconscious expression of the same confidence? We can’t just say that the conviction has to be a conscious version of Cartesian confidence to count as successfully picking out consciousness, or we would be engaging in circular reasoning.

Indeed, this approach to the exercise makes it almost impossible to come up with any coherent definition of consciousness that could be voiced by a zombie — but there are other ways we can play this game.

Imagine three different scenarios.

Scenario 1: God comes to you in a dream, asks you for your definition of consciousness, and writes it down. There’s no mention of zombies at this stage, and your definition is not contaminated by their impossibility. It’s just the definition you work from right now. Let’s suppose that your definition is compatible with the possibility of zombies. (Mine wouldn’t be, so, for me, this scenario can’t go any further.) God then creates a Zombie World lacking consciousness according to the written definition. You then check whether your zombie twin shares your definition of consciousness. It necessarily does, because it is in behavioural synch. That’s a major problem for your definition, because zombies can use the same words in their world while lacking the very thing you wanted to define. You have to watch while your twin erroneously declares that it possesses some special extra. If you’re lucky, God explains all of its false inferential steps, so you come away with an understanding of what it should have said, and hopefully that inspires you to review your own definition.

Scenario 2: God visits you as before, but, if you propose a definition of consciousness that is logically incompatible with zombies, God makes you change it. He says, “Sorry, I can’t work with that — a functional mimic of you can’t lack a functional aspect of your cognition; that’s a simple logical contradiction. Try again.” Now we’re back to the closing part of Scenario 1, but potentially it is some changed definition that is being shown up as faulty on the Zombie World, not your original definition. This time, if you are a functionalist, you don’t care how silly your twin looks. Or you watch with glee while the changed definition falters. You feel no ownership of the disaster.

Scenario 3: God comes to you in a dream, asks you for your definition of consciousness, and puts your answer in a sealed box. God then makes a Zombie World according to some hardist definition of consciousness. For instance, he creates a purely physicalist ontology without phenomenal spice. Is that really complying with the idea of a Zombie World? Is it really possible for God to make a Zombie World without confronting paradox or reneging on the rules of the thought experiment? You don’t care. That’s God’s problem. Other people are going to get the blame for your revelatory dream and for any attendant impossibilities. You only have to worry about cleaning up the mess the best you can, containing the damage.

Once more, you check what your twin says on that world, and it necessarily says exactly what you would say. So, what can it say without looking silly?

When I think of my zombie twin, I am working with Scenario 3 in mind. That’s the only scenario that truly tests my definition in a Zombie World without contaminating my views with hardist conceptions of spice. It’s the least corrosive option available.

I can’t get through Scenario 1 at all, and I only get through Scenario 2 by abandoning my own definition. In Scenario 3, though, I get to test my conception of consciousness in a world mandated to lack spice.

Hardists get their definition tested in all three scenarios, so these distinctions don’t matter to them. For a functionalist, though, the distinctions are crucial: only Scenario 3 provides any test of the coherence of a functional definition of consciousness on a Zombie World — even though that definition is not compatible with the existence of that world. For a functionalist to accept a definitional change sufficient to make zombies possible would be allowing the hardist conceptual framework to be more corrosive than necessary.

If a Zombie World is created by means you don’t have to worry about, by some ill-defined magical process that doesn’t change your sense of what consciousness is on this world, then you can start to think about what your twin should say about consciousness. And some answers survive this exercise better than others.

However you get to a Zombie World with your definition intact (and for me that is only via Scenario 3), your twin’s comments should be judged on their own merit, without regard for the fact that there is a Human World looking on.

At this point, your worry shouldn’t be that your zombie’s definition is the same as yours. A perfect definitional match is already guaranteed by the scenario, at least at the linguistic level, so there is nothing you can do about that.

Your worry should be that the zombie might say something that is stupid on its own world, making your views look silly by association.

Your definition of consciousness is in a sealed box, and your zombie twin is about to share its views (and yours) on the zombie version of Substack. What should it say?

I think you should be aiming to have a definition of consciousness in that sealed box that won’t embarrass you when your zombie twin repeats it. For instance, even if you possess phenomenal spice (because the thought experiment demands it), and the zombie does not, your definition should be indifferent to spice. You can’t possibly know about spice or draw on it for any conceptual content, so it should play no role in your definition even if it does exist on the Human World. You also want your twin to make no false inferences, so it should describe its model of mind without reference to spice; it can only justify what other zombies say on the Zombie World by describing consciousness as a representation that points to something a bit like spice — but without having any vindicating extra there on its world to act as a referent.

To avoid making unjustifiable claims, then, your twin needs to be somewhere on the spectrum that encompasses eliminativism, illusionism, virtualism or quietism. Your zombie twin can hold its head high if it adopts any position that rejects spice as a genuine ontological entity of relevance.

But the two of you are in cognitive lockstep, and neither of you has any evidence of spice. So you can only have a defensible position if your twin does, too.

In other words, your priority should be making sure your twin is not falling into the Zombie’s Delusion.

The Zombie’s Delusion

This blog is called The Zombie’s Delusion because I think that hardism, with its implicit acceptance of zombies, can be rejected on logical grounds. One way to reject it is through a proof-by-contradiction that involves imagining zombies.

I am not talking about what we might call physicalist-compatible pseudo-zombies; these are physical duplicates of humans who simply lack a special non-physical extra — an extra that physicalists didn’t believe in anyway, such that removing it doesn’t achieve much of interest. I don’t think creatures of that type yield a contradiction worth considering. Those are just humans by another name.

To get anywhere interesting in the conceptual neighbourhood of zombies, we need to imagine zombies who are missing an interior life, where the interior life that has gone missing has been considered in broad enough terms to capture whatever humans have. (I don’t think that’s logical, but we can try the idea on while keeping our own definition of consciousness intact, sealed in a box, safe from all this nonsense.)

The proof-by-contradiction will be the focus of later posts, and it is the connecting theme of this entire blog, so I won’t explore it in detail here. It can be summarised simply enough, though. Anyone arguing with vigour that zombies are possible must believe in a human-zombie difference worth talking about; the proponent of this difference must believe that they have good grounds to believe themselves on the fortunate, human side of this imagined divide.

Logic dictates that non-existent spice and epiphenomenal spice have identical effects on logical chains of reasoning: none at all.

A human brain, even when blessed with non-physical experience (spice), must be working off the same evidentiary basis as its zombie counterpart, receiving the same neural inputs, applying the same computational manipulations to the same information, and eventually producing the same spoken declarations of consciousness, with every word embedded in the same causal relation to the cognition that produced it. Spice doesn’t cause any divergence in neural activity between humans and zombies, by definition. It introduces no new chains of logic, it doesn’t create any branch points in the discussion. Even if the human version of consciousness is flavourful, this difference is entirely orthogonal to the processes that actually cause the human hardist and their zombie twin to declare their possession of spice and to argue for its existence.

It is as though we had two mathematical proofs, identical in form, with one of them written in rainbow ink. The colours can’t change the logical sequence.

The zombie twin of a hardist is necessarily wrong to think it possesses spice, so it must have drawn an unsafe inference from the information available. But the human hardist who professes belief in zombies has drawn all the same inferences from the same information. Even if the human hardist happens to be correct, and their thoughts really are shrouded in a special extra, they cannot have any safe grounds for deciding that they have won the ontological lottery while their twin has not.

This is a point conceded by Chalmers in The Conscious Mind:

Now my zombie twin is only a logical possibility, not an empirical one, and we should not get too worried about odd things that happen in logically possible worlds. Still, there is room to be perturbed by what is going on. After all, any explanation of my twin’s behavior will equally count as an explanation of my behavior, as the processes inside his body are precisely mirrored by those inside mine. The explanation of his claims obviously does not depend on the existence of consciousness, as there is no consciousness in his world. It follows that the explanation of my claims is also independent of the existence of consciousness.

To strengthen the sense of paradox, note that my zombie twin is himself engaging in reasoning just like this. He has been known to lament the fate of his zombie twin, who spends all his time worrying about consciousness despite the fact that he has none. He worries about what that must say about the explanatory irrelevance of consciousness in his own universe. Still, he remains utterly confident that consciousness exists and cannot be reductively explained. But all this, for him, is a monumental delusion. There is no consciousness in his universe—in his world, the eliminativists have been right all along. Despite the fact that his cognitive mechanisms function in the same way as mine, his judgments about consciousness are quite deluded.

(The Conscious Mind, Chalmers, 1996, emphasis added.)

Because their zombie twins are necessarily deluded, human hardists who promote the idea of a Zombie World turn out to be building something of a conceptual trap for themselves.

If a Zombie World existed, it would falsify physicalism when held up in comparison to a Human World, because the human-zombie difference (spice, Δ) would necessarily go unexplained.

But the Zombie World is also a world that superficially resembles ours, and it gets along entirely without spice, so it forces us to consider the role of spice in producing the hardist framework. And that role turns out to be non-existent.

Homo sapiens are still the dominant intellectual species on the Zombie World, their IQs show the same distribution, and the rules of logic have the same status. Zombies still debate qualia and they have something they call a Hard Problem, supported by all the usual hardist arguments. Those arguments are not motivated by spice; nor are they capable of proving its existence. All hardist arguments on the Zombie World run their cognitive course and have their cognitive impacts for purely functional reasons.

As Chalmers notes, a Zombie World is a world in which the eliminativists have been right all along. A Zombie World is a world in which anti-hardists have been correctly arguing that the hardists were getting confused by some aspect of their own cognition, and the hardists have been deludedly positing spice to fill cognitive gaps.

In other words, the Zombie World is a world very similar to our own, and everything I want to say about consciousness on this Human World is simultaneously being said by anti-hardists on that Zombie World, but with the uncertainty removed by the scenario designers. The anti-hardists on a Zombie World are right by definition (except, potentially, in their insistence that Zombie Worlds are impossible, but, even then, their definition of a Zombie World refers to a world one rung down on an endless ontological ladder, and they are right about the incoherence of that Meta-Zombie World).

Spice on the Zombie World is not just a bad idea for all the usual reasons; it is officially no more than a hardist fiction. The inability of spice to play any relevant role in the conceptual story has been rendered as unambiguous as possible, and yet the argument about spice continues unchanged. The hardists on a Zombie World are necessarily straying from safe inferential logic; because spice is non-existent, and yet they conclude it must exist; they necessarily draw this conclusion from non-epiphenomenal sources misconstrued as epiphenomenal. And there are functional reasons for that misconstrual.

By contrast, the anti-hardists on the Zombie World are staying within defensible limits.

Of course, the cost paid by the zombie anti-hardists to exist in this officially sanctioned state of being 100% correct is that they’re dead inside, which is a price none of us would be happy to pay — but that’s not my problem, and I couldn’t convince my zombie counterpart he was missing out on anything important. I have no good reason to think I am not the zombie in this scenario (apart from my insistence that they are impossible, but that opinion has been temporarily overruled).

Furthermore, I don’t actually believe that zombies are missing out on anything important, because, as a physicalist, I necessarily believe that what they do have is sufficient for the appearance of a rich interiority.

The supposition that zombies might exist leads to the conclusion that the supposition itself can have no reasonable defence.

To be completely honest, it is not entirely clear to me what I need to do to imagine the Zombie World in a manner that would satisfy the contract of this thought experiment. I’m not really cut out for it. Imagining a zombie, for me, will always be a half-hearted exercise because I can’t shake off the knowledge that I am heading for the Zombie’s Delusion.

If my zombie twin did exist, he would live in a world that is mandated to have a simple ontology, without any special experiential extras — but that’s what I think about this world, anyway, so I struggle to think of ways in which my zombie could be legitimately different to me. My twin has no special inner light, by definition, and neither does anyone else in his barren universe, but I don’t think we possess a special inner light, anyway. (At least, I don’t think we have anything conforming to the hardist notion of phenomenal spice, conceptualised as a human-zombie difference.)

Imagining that the Zombie World lacks phenomenal spice, when I don’t even believe in spice on this world, seems a bit like cheating — all I have done is call it a Zombie World, while imagining its ontology as identical to what I already believe is the basis of this world.

But what choice do I have? Ostensional consciousness (Σ) is notionally a combination of two sets of entities: functional elements that I think are sufficient for explaining consciousness (ρ), and disputed extras I think make no sense (spice, Δ). If I am imagining that zombies lack spice (Δ), when I already believe that we all lack spice, the imaginative exercise has no real impact on physicalism; I am imagining two identical worlds. And I can’t imagine that the functional elements of consciousness (ρ) are missing, because that would lead to a divergence in behaviour.

So what do I have to imagine? I think consciousness is a representation, but that’s a functional notion. Imagining that zombies lack the functional basis of a represented inner world is not consistent with the rules of the thought experiment, because they are supposed to be our functional mimics. Their internal representations have a complex set of relations to the causal network that they call reality, and our own representations have the same relationship to the causally relevant parts of our supposedly richer reality. To remove those representations in the zombie’s case, I would have to do physical violence to the relevant neural circuits, and that’s disallowed.

In practice, there are workarounds, as long as I don’t think too hard. I can call my twin’s inner world “a mere representation”, and imagine that it is dark inside his skull, which is probably what hardists do. The problem is, I already think our inner world is merely represented and that it is literally dark inside our skulls, so this still feels a like I am not entering into the spirit of the thought experiment.

To really imagine a Zombie World, I must channel my hardist intuitions, and I must willingly commit to conceptual conflations that I have decried elsewhere. I must imagine that the zombies are only missing spice to keep them in behavioural synch, but that’s not removing anything I think is important, so I need to cheat a little. I must employ contentful concepts to imagine them as different to human, while knowing that the content I’m employing can’t come from spice.

(In other words, I have to sneak a little ρ into my Δ; I need to remove represented content from their interiors while telling myself I have not touched the representational medium, jumping deftly between ρ and Δ. If these symbols mean nothing to you, please read this earlier post. )

The most important thing I can do when trying to imagine a Zombie World as a hardist might is to project an empty void onto every humanoid inhabitant, refusing to imagine their interiors as anything like the colourful interiors we seem to enjoy. Then, when I’m imagining the causes of the zombie’s behaviour, I need to focus on the blind unconscious mechanisms of individual neurons while ignoring the potential for those neurons to model anything of interest.

Those are all tactics adopted in my head, with no real consequences on the Zombie World, but it is the best I can do.

Let’s assume that I have tweaked all the relevant cognitive dials in the appropriate directions, and I am now imagining a Zombie World as well as any hardist. I firmly believe in spice and I imagine that zombies, lacking this special extra, have dark, wet interiors inside their skulls, and that’s all they have. The rest of their so-called minds are merely represented. (For more details, try reading the post where I imagined a zombie with as much sincerity as I could muster; that post won’t contain much that is new to seasoned travellers in this field, but it is potentially useful for beginners.)

Are these various tweakings and hardist-inspired imaginings now part of my definition of consciousness? If so, then I have generated a concept of consciousness that is potentially in trouble, but it is not really my own definition any more; it is not the one I sealed in a box before launching into this exercise. The corrupted definition is simply what was needed to create the imagined Zombie World.

Moreover, most of the tweaking has involved ramping up the importance of spice on the Human World, and so it does not make much difference to how I view the Zombie World, where my definition is not in very much trouble at all.

(Note that, after this conceptual readjustment, the Zombie World is ontologically close to where I started, and it is the Human World that has acquired hardist fictions, so the debate about whether zombies are possible really should be recast as a debate about whether a meaningful human-zombie difference is coherent. Creating an incoherent extra and then removing it takes us in a circle, letting hardists inherit the appearance of coherence from a physicalist conception of reality.)

There are now two definitions of consciousness in play, the one based on the Human-Zombie Difference (which I have grudgingly imagined as being operational but actually think is nonsense), and my original true belief (which is totally untouched by this exercise, just as the nature of pi was actually untouched by our student’s dream at the start).

This is the point at which Mandik and I turn out to be addressing different forms of the question. To me, a Zombie World can only ever be a world that notionally differs from ours along a dimension that hardists believe in and I reject; that difference does not corrupt my own definition, which is transported along the illusory dimension unchanged.

If God came to me in a dream and told me that spice exists and that it was epiphenomenal, and he was about to launch Scenario 3, I would still struggle to see the relevance of spice to anything I might want to say about consciousness, because my interest is in things I can know about without relying on revelatory dreams.

So, here I am, imagining a Zombie World, which is filled with beings that are dead inside in some special way. They definitively lack spice, without knowing that they lack it. Sucks to be them.

Spice is epiphenomenal, so the zombies’ cognitive relations to their physical world are identical to human relations with our physical world, even if our situation is imagined as having some additional flavours. Like the rainbow ink considered earlier, those extra flavours stand outside the causal networks to which we have access, so they have no impact on what we can safely conclude about our world, and the lack of these special extra flavours is undetectable on the Zombie World.

We and our zombie twins have no reason to draw different conclusions about anything.

Nothing about the Zombie World should impede the zombies’ collective and individual ability to do good science. One zombie might report, after a trip on the HMS Beagle, that it has solved the mystery of apparent design in biology. Another zombie might reconceptualise gravity as curvature in spacetime. Another might describe action potentials in neurons; another might study synaptic changes as a mechanism for encoding memory.

Zombies on that hypothetical world could not only study the zombie brain from a third-person perspective, but also from an (unconscious) first-person perspective. Optical illusions would still need to be considered in cognitive terms to make sense, from the perspective of the cognitive system getting misled. Zombies would still need a theory of mind to achieve success on their world, even if they are theorising about something that is ultimately unimpressive from a God’s Eye view of both worlds side by side, one that sees the richer version of minds on our world. Zombies could perform the cognitive act that we call introspection and, even if this act goes on in the experiential dark (whatever that means), they will find reportable features of their cognition.

Inevitably, teams of zombie scientists will devote their life to the study of various puzzling features of their own cognitive systems.

The zombie scientists will eventually come to the challenge of defining “consciousness”, even if we choose to see this word as relating back to no more than a complex functional entity behind a motor act.

Zombie scientists and philosophers will immediately confront a mismatch between how they model consciousness within their brains and where the objective perspective of science takes them. We know this because they write about this mismatch, talk about it, and so on — which we know because we write about it and talk about it, without any of our motor acts or arguments being motivated by spice.

Those zombie students of consciousness would end up drawing diverse conclusions about their world and its simple ontology. Some of them will become hardists, some anti-hardists, some idealists, some illusionists, and so on. Even if all of that cognition is bland in some poorly defined way that is important to us, there are still right and wrong answers about zombie neuroscience, just as there are right and wrong answers about the source of apparent design in zombie biology, the nature of gravity in the zombie universe, and so on.

Their science is not invalidated by their lack of spice; there are still right and wrong answers about the way things are on their world. It is conceivable that the Human World might never have existed, and the struggle to understand the Zombie World would be unchanged by our non-existence.

That means we can ask: What scientific conclusions should a clever zombie draw about the ontology of the Zombie World?

Personally, I think clever zombies should decide that spice is nonsense and Zombie Worlds can’t exist.

That might seem awkward, and some of that awkwardness is captured in Mandik’s post.

My own zombie twin would necessarily express the belief that zombies can’t exist, and he would necessarily be wrong by virtue of his own existence — but that’s only by virtue of being caught up in this hypothetical, and he has no proof of his zombiehood. For better or worse, we’ve mandated that this hypothetical situation is true, even if it is silly. If a Zombie World is actually an impossible situation, but we’ve gone ahead anyway and decreed that its possible, we’ve arbitrarily inverted the truth value of everyone’s belief about zombies for the duration of this thought experiment, making fools of some theorists on both sides of the human-zombie divide, and giving others a free pass that they haven’t really earned.

On a hypothetical anti-math world where 2+2=5 but everything else is unchanged and assuming we leave no experimental evidence of maths’ perilous condition, most of our anti-math twins will continue to express the belief that 2+2=4. They will be wrong in that belief — unless they are mathematical morons prone to saying that 2+2=5, making a mistake that happens to cancel out our externally decreed truth inversion. The most defensible answer to the addition of 2 and 2 would still be 4, which turns out to be the wrong answer, for reasons we can’t really specify, but that’s our fault for inventing a world where defensible beliefs have had their logical underpinnings arbitrarily corrupted by our wicked design.

So, my zombie twin is 1) necessarily wrong about the possibility of zombies and 2) dead inside. Those are both major hits to his credibility when it comes to speaking on the topic of consciousness, but these problems are not conclusions we have drawn from analysing the Zombie World; we’ve simply accepted them going into the scenario.

Putting those two issues aside (because my twin shares none of the blame), what should he say about the ontological nature of what zombies call consciousness? Given the ontology he has to work with, and the evidence available, what is the most rational approach for him to take?

Should any rational zombie conclude that it is dead inside in some way that would make it less than human?

The answer here must be no, because if it is your twin, or mine, it can’t draw that conclusion. It is behaviourally identical to a human, so it will say what its human counterpart says. Your twin will say all the things that you say. My twin is writing this blog post and it would say, if asked, that it enjoys the appearance of a rich interiority, that it doesn’t feel dead inside.

We are in cognitive and behavioural lockstep with our zombie twins. Your zombie twin will only act as though it lacks consciousness if you are unconscious — or pretending to be. Any conscious human sincerely declaring that they are dead inside is someone in need of an urgent referral to a psychiatrist. Delusions of inner deadness can occur in the human world, unfortunately, but they are rare. They are identically rare in the Zombie World.

Should any zombie conclude that it houses a special spark of phenomenal consciousness? We can’t just decide that a rational zombie will correctly reject this answer because it is a zombie; the zombie has no access to the meta-view that would tell it that it exists within a special thought experiment where special sparks have been decreed to be locally absent. It will have to choose between hardism and anti-hardism based on the available evidence and principles of parsimony, and so on.

We need to consider whether there can ever be any good reasons for the zombie to declare belief in phenomenal spice. And we’ve seen this debate before. We know what a zombie hardist will argue. Would it be rational for a zombie to appeal to the Zombie Argument, imagining zombies as some lesser being? I don’t think so, but working out why it might believe this would be instructive. Would it be rational for a zombie to consider the fate of a zombie colour-scientist locked in a black-and-white room, and then conclude that the scientist would learn something on being exposed to coloured inputs? Opinions on this question might diverge. (I think the answer is rather obviously yes, the scientist would acquire new neural states and learn something, but this is essentially an empirical question; it would take much more work to consider the various arguments on either side.) More importantly, in a world without spice, is there any sequence of physical events in the colour scientist’s life that could give it convincing evidence of spice?

And again I will say no, because spice that does not exist can’t produce evidence of anything — and the same is true of spice that does exist.

If anyone on the Zombie World concludes that they have intuited the existence of spice, then that intuition has come from an unreliable source. But the intuition must have come from somewhere, if this scenario is to have any plausibility at all: it can only have come from the cognitive structure of the zombie’s brain and its tendency to model things that don’t exist. The scenario itself relies on the zombie’s physical brain modelling an interior mind that does not exist, which necessarily means that human brains are functionally inclined to do the same thing, independently of whether those models are vindicated.

A clever zombie will realise all of this, and its eventual spice-free theory of consciousness is one that most physicalists should be happy to sign off on.

That spice-free theory is the subject of this blog.

We started with the question: “Is it a problem for your definition of phenomenal consciousness if zombies agree with it?”

There is no right answer here. I think it’s one of those situations where, if you agree to swallow an impossibility for the sake of the argument, it’s somewhat arbitrary as to which parts of your framing you should break to accommodate the resulting incoherence. We’ve already broken logic, so to some extent it no longer matters.

When you invite an impossibility over the threshold, the important bit is not where the fault comes to lie; what matters is seeing the contradiction and recognising that something is wrong.

But I will continue to apply the following test, and I think you should, too:

Would I be embarrassed if any of my opinions of consciousness were repeated in what was known to be a minimalist physical world without spice? Have I adequately factored in the spurious functional sources of belief in spice?

Am I a victim of the Zombie’s Delusion?

Cool article. Since you mention me, I thought I’d respond. Apologies for being long-winded, but I hope this is constructive and helpful. Classical philosophical zombies (pre-1990s philosophical zombies) are stipulated to be physically identical to phenomenal consciousness havers while not themselves being phenomenal consciousness havers. Classical zombies by definition lack phenomenal states. The classical definition of zombies is silent about whether zombies, despite lacking phenomenal states, might have other mental states. If it’s possible to have intentional states such as thoughts and judgements without having any phenomenal states, then the logical possibility is open for philosophical zombies to have judgements. Dennett attempts to exploit this in 1991 to argue against anti-physicalist approaches to consciousness. He devises a thought experiment of zimbos. Zimbos are philosophical zombies explicitly defined as having non-phenomenal intentional states such as thoughts and judgements. Dennett exploits the fact that if zimbos can have judgements, then they can have judgements about phenomenal states. He uses this to try to construct a reductio of antiphysicalism. Chalmers grapples with the same problem in 1996 and labels it “the paradox of phenomenal judgement”. The problem/argument goes like this. It is widely supposed that we know, and know with certainty, that we are conscious. But, just like external world skepticism ensues if you can have a belief about the external world without the belief being true (because, then, for all you know it’s false), so then can internal skepticism ensue: If judgements about phenomenal consciousness can exist even in beings who lack phenomenal consciousness, then for all we know the zombies are us. The paradox/contradiction is that if antiphysicalism is true we both know and do not know that we have phenomenal consciousness. The “solution” that many antiphysicalists are attracted to is to deny that zimbos are possible. Zombies are still possible according to these antiphysicalists, but zimbos are not—they insist that, lacking phenomenal consciousness, none of their brain states are actually judgements about phenomenal consciousness. Perhaps they don’t have judgements or thoughts at all. This does indeed block the paradox/reducto. Their story is that they are directly acquainted with their own qualia. This acquaintance reveals to them what consciousness is—their concept of consciousness (according to them) correctly represents what consciousness is. And so, when they (according to them) conceive of physical beings lacking phenomenal consciousness, they have knowledge of a real possibility, and (according to them) physicalism is false. What is the antiphysicalists definition of consciousness? They’ll tell you they don’t have (a noncircular) one, and that they don’t need one. They just directly introspect their, arguably nonphysical, phenomenal consciousness. And zombies, according to them, might utter the same words, but those zombie utterances don’t express actual thoughts. Anyway, the point of all this is to say: I don’t claim it’s a problem if your definition of phenomenal consciousness can be agreed to by zombies. I claim instead that it’s a problem if you’re advertising your definition as NEUTRAL with regard to the key debates and it can be agreed to by zombies. Antiphysicalists who have responded to zimbos/the paradox of phenomenal judgement in the above manner will say that zombies do not agree to the definition, they simply utter words that sound like agreement. The person claiming to offer a neutral definition can’t say that. They can’t because they would then be taking sides and thus not being neutral. And if the so-called neutral definition provider says that phenomenal consciousness lackers must be ignored in evaluating the definition, then what the provider is saying becomes circular, since they would be using the concept of phenomenal consciousness in their statement of what phenomenal consciousness needs to be.