Triplism, Part One

A.k.a. Introduction to Virtualism, Part #4

Three shall be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shall be three. Four shalt thou not count, neither count thou two, excepting that thou then proceed to three. Five is right out. (God, 1975, via Monty Python and the Holy Grail.)

Discussions of phenomenal consciousness usually orbit around some form of dualism, and hence around two concepts: body and mind, access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness, spike trains and qualia, zombie bodies and human extras.

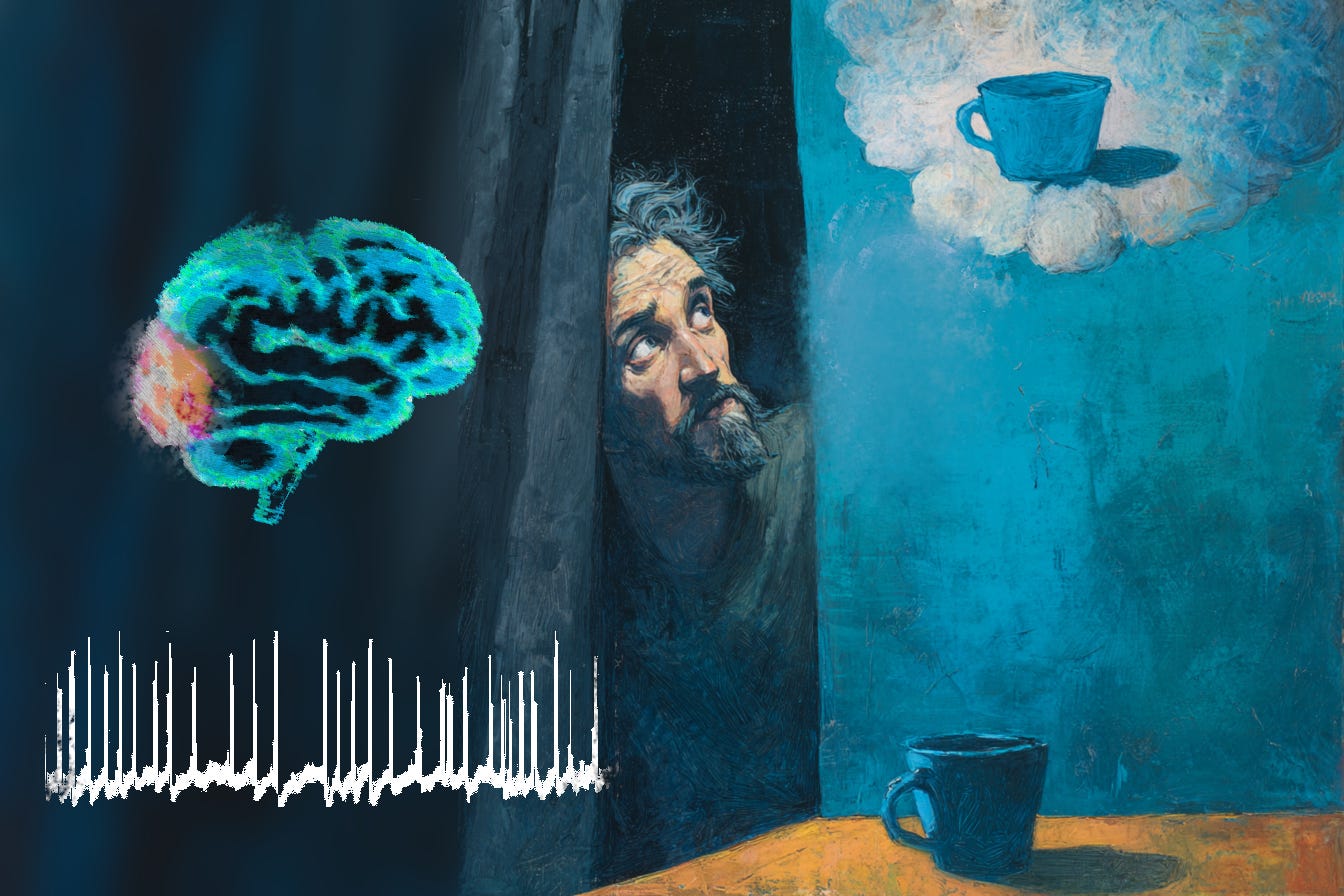

I want to make the case that we need three conceptual entities to discuss any type of phenomenality sensibly: 1) the neural substrate of a phenomenal concept; 2) its implicit content; and 3) a hypothetical vindicating target.

To illustrate these three conceptual entities and the confusion that attends them, consider Daniel Dennett’s paper, “Illusionism as the obvious default theory of consciousness” (2016).

It’s a good paper, which I mostly agree with, and Dennett was a brilliant philosopher who contributed greatly to my overall understanding of the mind. Indirectly, he helped push me into clinical neurology.

But I have an important nit-pick.

Dennett discussed the after-image one might see after staring intently at a colour-reversed American flag. On looking away, the black, green and yellow of the real image are reversed to create a correctly coloured after-image. This is one way of approaching the idea that consciousness and its contents must involve some form of illusion, because what is it that is red, white and blue in this scenario? When the observer in the grip of this illusion perceives a red stripe, what in reality is red?

Where a hardist will typically want reality to furnish something that actually has the perceived red colour (or has some phenomenal mental equivalent of redness, something that is like redness, something that really seems red), Dennett is content to call the redness illusory.

When you seem to see a red horizontal stripe (as a complementary-colour after-image of a black, green, and yellow American flag), there is no red stripe in the world, no red stripe on your retina or in your brain. There is no red stripe anywhere. There is a ‘representation’ of a red stripe in your cortex and this cortical state is the source, the cause, of your heartfelt conviction that you are in the presence of a red stripe. You have no privileged access to how this causation works. […]

The red stripe you seem to see is not the cause or source of your convictions but the intentional object of your convictions. In normal perception and belief, the intentional objects of our beliefs are none other than the distal causes of them. I believe I am holding a blue coffee mug, and am caused to believe in the existence of that mug by the mug itself. The whole point of perception and belief fixation is to accomplish this tight coalescence of causes and intentional objects. But sometimes things go awry. […]

What are intentional objects ‘made of’? They’re not made of anything. When their causes don’t coalesce with them, they are fictions of a sort, or illusions. [Emphasis added.]

Just as I did in my last few posts, Dennett draws a distinction between the source of a concept (its “distal causes”) and its target (the thing the concept is about). Here I am using the word “concept” in a broad but brain-focussed sense to cover contentful mental states, including perceptions. A key point is Dennett’s reference to normal veridical perception, where source and target are so tightly aligned that we don’t usually see a need to distinguish between them, and his observation that this alignment can go awry.

That misalignment is why we need three notional entities to cover the situation.

Unfortunately, I find myself agreeing with Dennett’s intent, but not his chosen words, because his phrasing illustrates the very confusion I want to talk about.

Consider the conflict between these lines:

“In normal perception and belief, the intentional objects of our beliefs are none other than the distal causes of them. I believe I am holding a blue coffee mug, and am caused to believe in the existence of that mug by the mug itself.” [Here, the intentional object is the distal cause, which is the ceramic mug.]

“The whole point of perception and belief fixation is to accomplish this tight coalescence of causes and intentional objects.” [Now, the intentional object is something other than the cause, but the two can be coalesced — perhaps conceptually, perhaps terminologically.]

“What are intentional objects ‘made of’? They’re not made of anything.” [In the final paragraph, the intentional object is not made of anything, and it is therefore not ceramic; nor can it cause beliefs or anything else.]

In consecutive paragraphs, Dennett states that intentional objects are none other than the distal causes of our belief and also that intentional objects are not made of anything. Both of these claims cannot be simultaneously true, because the distal causes of our belief have to be made of something to enter the causal game.

When Dennett believes he is holding a blue mug, the distal cause of his belief is the ceramic mug in his hand, so the intentional object (being “none other than” that distal cause) must be the ceramic mug. But he also states that intentional objects are “not made of anything”. Ergo, he is holding a cup that is not made of anything, and he is at risk of spilling his coffee.

What’s gone wrong?

I am not suggesting that Dennett misunderstands anything in these passages; I am saying that the available language lets him down, and he has — perhaps inadvertently — made a good case for new terminology. We shouldn’t accept language that fails to distinguish between the source and target of mental states, because it leads to silliness of one sort or another. This superficial linguistic conflation between two meanings of “intentional object”, found in the words of someone who does understand the difference, is of the same basic flavour as the source-target conflation at the heart of hardism, where it is not usually acknowledged and contributes to on-going confusion.

Dennett proposes that there is usually a tight coalescence between these different versions of “intentional object”, and I fully agree, but that coalescence does not provide us with a good reason to use an ambiguous term – as his red stripe example illustrates nicely.

When it comes to imagining that the intentional objects of our phenomenal concepts – “phenomenal consciousness” and “qualia” – might go missing in a zombie or might end up being left out of a textbook account of physical reality, we need to know which reading of “intentional object” is in play. The conceivability of zombies generally requires that we overlook this distinction, because when we imagine them we must pivot from: 1) the source that gave our phenomenal concepts content; to 2) the imaginary target that cannot influence our thoughts because its removal, by definition, must be behaviourally and cognitively invisible – though few fans of zombies would express things this way, because of the very conflation at issue.

Now, it just so happens that I habitually drink my coffee from a blue mug; my wife drinks from the green ones. As I’m writing this, a real blue mug is on the table beside me, a situation that can serve to illustrate the three entities of interest: my neural model of the mug, the implicit content of the model, and the physical mug.

Both the implicit content and the physical mug lay claim to being the “intentional object” of my neural model.

None of this should be confusing. When I look at the physical mug, some of the light bouncing off it enters my eyes, is focused by my lenses, and reaches my retinas. Detailed spatial information about the mug is preserved in the pattern of photon arrivals. My retinas do the initial conversion from the domain of the real to the domain of the represented: photons stimulate chemical reactions, changing the firing rate of retinal receptors, and neurons subsequently carry the information forward as electrochemical action potentials, or spikes. Henceforth, downstream from the retinas, neural signals coming along the optic nerves can be treated as a stand-in for light or, more often, as a stand-in for the cup itself. Spatial and colour information about the physical mug gets encoded into neural traffic in the visual system, which means that much of the higher‑order neural activity downstream from the initial photon‑to‑neural interface can be treated as a virtual image, even though it is no longer anything like a picture in terms of its spatial or physical properties (and obviously it does not need to be projected onto some internal mind‑screen to be re‑seen all over again).

To interact coherently with the represented mug, everything else in my cognitive structure must also work within the represented domain. The cognitive sub-system that plans for motor acts like reaching for the mug is part of the same representational economy that initially accepted optic-nerve neural activity as an acceptable stand‑in for eyeball photon patterns, which were themselves in causal linkage with (and therefore informative about) the actual ceramic mug.

If we follow this logic of substitution into the wider and more complex systems of memory and attention and goals and language, and we insist on consistency, we’re led to the conclusion that all of my cognition is in the form of neural activity that is representative of other things, including my virtual cognitive grasp of the represented mug in my virtual bubble of consciousness. It would not make much sense for my attentional grasp to reach out through represented space if it were not itself part of the broader representation.

If I decide to drink from the mug, my motor cortex (in conjunction with the spinal cord and other subsystems) will choose a set of muscles for the task, working from a neurally encoded spatial model of my body and the environment. That model and all the attendant calculations operate with a represented three‑dimensional space that is about real space. The motor system will help convert my neurally‑encoded goal, picking up the mug, from the represented domain to the real domain. The final represented‑to‑real translation can be arbitrarily considered as taking place at the motor end-plate, where neural signals trigger the release of chemical signals from the motor neurons, making the chosen muscles contract. Lo and behold, I pick up the real mug, although my cognition has only ever dealt directly with its quasi‑existing neural shadow.

In practice, this story is a simplification; there are likely to be several such loops around the real‑to‑represented‑and-back-to‑real circuits of my brain, as my eye takes in multiple visual gulps of the mug, and my motor system titrates its movements, and Bayesian inferential processes make useful simplifying assumptions about the physical world. The virtual and real worlds are in a state of constant interaction and adjustment, and all of those interactions bind the mind to the world in a way that constantly reinforces and validates the link between the represented and the real.

I have suggested that the borders between real and virtual lie at the retina and motor end-plate, but this is an arbitrary stipulation and we could locate the translation steps differently. We could argue that most of the translation from real cup to represented cup was actually achieved by the physics of light reflection, which converted a ceramic object into an informative stream of photons. We could also identify parts of the motor system proximal to the motor end plate that could be understood as operating within the domain of the real rather than the represented. Cut a motor nerve, for instance, and the resulting difficulty will be manifested in real space with real weakness, making no direct difference to the formation of motor plans or the imaginative manipulation of the represented cup. In other words, the borders are fuzzy; the account I have offered is cartoonish. But the essential point is that my entire cognitive life takes place in the represented domain between real‑to‑represented sensors and represented‑to‑real actuators. Indeed, how could it be otherwise?

On the representational side of the border, within my head, nothing is actually like the thing it is about: neural spikes or populations of activated neurons are not photons, or mugs, or planned motor acts within a literal three‑dimensional space. The powerful dualist intuition, which says that soggy grey matter is the wrong type of stuff to be all those things, is therefore perfectly justified, but it simply doesn’t matter, because the rest of my brain is content to treat neural activity as photons, and mugs, and motor acts. If all the neural systems agree on this convention, there is no contradiction or complaint on the representational side of the border. Something that is actually impossible if interpreted literally – neurons being mugs, and so on – is quietly accepted as a useful working convention. Of course my brain accepts its representations as real, because most of the acceptance is hard‑wired, there are no strong indicators in my day‑to‑day life that I am wrong, and all of the representational conventions serve me perfectly well.

I walk around in a perpetual bubble of virtual reality, my brain fed an informational stream of spikes and nothing but spikes, but my body does all the necessary conversions between real and represented, handling the representational twists as needed, so the interaction with reality is largely seamless.

It is like converting gold to paper money at one border, travelling across the continent, and then changing it back to gold at the other border. During my journey, paper can break all the rules of metallurgy but be gold in every sense that matters financially. A hypothetical hard problem of explaining how paper can give rise to gold would not bother anyone too much, much less inspire demands for a new physics of paper, but it is analogous to many aspects of the Hard Problem of Consciousness.

We know the points of exchange from real to virtual and back; we don’t need to be confused, and we should expect border-crossing questions to run into difficulties.

It might seem odd to some readers for me to suggest that there are, in effect, two mugs involved, one represented, and one real, whenever I am looking at a single physical mug. It seems fair to ask: “Isn’t there just one real mug and the brain thinking about that same mug?” But it will be important to distinguish the relevant concepts with the simple case of a mug before judging the much more puzzling status of consciousness, where the tight coalescence flagged by Dennett goes awry.

We’ve already seen how even Dennett uses ambiguous terms that collectively implied he was holding a non-physical mug, even though he was not at all confused and the two mugs were in close agreement. If we allow confusion to enter the framing with such a mundane example, we will only suffer all the more later on.

Still not convinced? Some simple thought experiments expose the need to distinguish between the two mugs under consideration. If I got a migraine, for instance, my mind‑mug might fracture or develop a shiny zigzag border, while the real ceramic mug remained unaffected; this is the first clue that the mind‑mug is not the same mug as the ceramic mug. Or the real mug could have a huge crack in it, hidden by my line of sight, while my mind‑mug remains whole in my imagination.

Or imagine that, before I pick up the mug, someone places a curtain between me and the real mug, but I continue to think about the mug, which is now hidden by the curtain. The mug was originally blue but, behind the curtain and without my knowledge, someone uses spray paint to change the real mug to hot pink and also uses laser to silently remove the handle. There is now a blue mug with a handle in my mind, but a pink mug without a handle on the far side of the curtain. Things are going awry; we have two mugs, only partially matching.

Note that physical events on my side of the curtain can affect my virtual neural shadow of the original mug, but they cannot affect the real mug itself. Physical events on the far side of the curtain can affect the real mug, but they cannot affect my mind‑mug unless I see or hear the events or obtain the updated information via other means, such as language. Changes to the real mug must directly comply with the laws of physics as they pertain to mugs; when the real mug fractures, for instance, it does so in a physically plausible way, conserving mass and energy and creating shards that could be put back together to form a whole mug. Conversely, changes to my mind‑mug (in response to a migraine, drugs, or neurological lesions) could be arbitrarily odd, with weird migraine‑related fractures or psychedelic doublings that ignored the laws of conservation of mass and energy, because on this side of the curtain, the laws of physics only apply to the neuroanatomical substrate of the representation, not to the represented mug itself. (The mind-mug is subject to fake physics, and it would be foolish to apply scientific considerations to that fake physics directly. Later, I will say the same of consciousness itself.)

All of these considerations imply that it makes sense to say, even prior to placing a curtain between me and the real mug, and even without making any of the suggested changes to either mug, that there are two entities worthy of the name “mug”: there is the real mug and its neural shadow. Usually, as Dennett notes, these two entities remain in a tight causal relationship, and either can be plausibly referred to as the “intensional object” of my thoughts, but they are different intentional objects. Provided that the mind‑mug is viewed from the perspective of the cognitive system that accepts the represented mug as it seems, the two mugs share so many properties that the neural‑shadow‑mug can be said to be about the real mug, and only a philosopher or a neurologist would ever worry about the distinction. (From a different perspective, of course, the structures that represent the mug are not mug‑like at all; they are collections of neurons firing in the dark, interacting in complex ways that would be largely opaque to all but the most advanced neuroscience, and far removed from the simple fluid-holding physics of real mugs.)

Changes on either side of the curtain could affect the accuracy with which my mind‑mug remained a copy of the original mug, and, if the inaccuracies became severe enough, we could say that my mind‑mug was no longer about the real mug, but was its own independent fiction – perhaps with the footnote: Inspired by a true mug.

Does that mean, when we are looking at a mug, we are actually looking at or thinking about its neural shadow, not the real mug? No. Treating perception as a two‑stage process – involving a first stage in which we look at and think about incoming sense data and a second stage where we extrapolate outwards to an external object – has been dismissed by most philosophers as an unnecessarily cumbersome way of describing perception, and some philosophers refer to belief in this two‑step process as the sense‑data fallacy. The fallacy consists of the false notion that our conscious thoughts are about the sense data coming in or about the neural representation rather than about what they seem to be about. This is not a natural way of describing what is happening, and it is not what I am suggesting (though certain sub‑processes in the brain, such as edge-detecting circuits, are usefully thought of as being about features of the sense data rather than about the mug). There is also good evidence that the entire process of perception is collaborative, with a stable percept emerging from agreement between multiple systems including top-down semantic effects. Optical illusions prove that we don’t maintain awareness of raw sense data, and we can be quite mistaken about features of the raw, uninterpreted information stream.

So we are not looking at the neural shadow. The natural target of my mug‑related thoughts is still the real mug, and “looking” still means what it has always meant in natural language; I’m looking at the real mug. That’s the whole point of the visual system, to let us look at, represent and think about external reality. In the ordinary case where I am not engaging in philosophical speculation, and I’m just looking at a mug, I don’t think about the neural model at all; it could be said that I think with the neural‑shadow mug, which is what enables me to think about the real mug.

It would also be a fallacy to imagine that the internal representation consists of some form of phenomenal mug image or mug-like entity that is projected onto some internal mental screen, complete with phenomenal blueness, to be seen a second time; this mistaken notion is sometimes tied to the sense‑data fallacy, and sometimes to what is known as the phenomenological fallacy, in which mentality is conceptualised as having the properties that are merely represented. (Chalmers, for instance, talks of “blue experiences” and “red experiences”, seeming to embrace this fallacy without restraint.) This cluster of fallacies is also part of what Dennett derided as the mistaken view of a Cartesian Theatre.

Despite the illustrations accompanying this post, I am not proposing anything so literal as a mug-like entity in the mind. The virtual mind-mug is a mere potentiality, a way of interpreting neural firing patterns; it does not exist directly as it seems; it does not even have the appearance of a blue mug.

Those familiar with the many complex stages of neural visual processing might offer a completely different criticism of my proposed two‑mug schema: two mugs are not enough. There is no single mug representation in cognition; there are myriad representations at multiple stages of processing, subject to continual revision and top‑down influences, and so on. We could, potentially, extract mug‑like representations from many different sites in the multi‑stream flow of visual information: from the retina, from the optic nerve, from relay stations in the thalamus, from the occipital cortex, and elsewhere. We might find a dozen or more mugs in various states of analysis, or a cubist mess of angles and partial mugs and competing hypotheses. This is true, but it merely means that the mind‑mug needs to be considered as a complex, flowing representational entity that influences and is embodied by a number of interacting neural subsystems, many of which are well below conscious awareness, and the mind-mug emerges in the form of a neural consensus about what’s on the table before me.

For all these reasons, picturing the internal cognitive representation of a mug as a simple mug in the mind is an obvious caricature – there is nothing very mug-like in the mind – but this caricature is also a fair example of such a mind‑mug, in the sense that many of the same mug‑representing circuits are likely to be activated when we think of the idea of a mind-mug in this cartoonish fashion as when we think more directly of a ceramic mug. We don’t err when we think that a mental model of a mug is like “this”, picturing a mug as we do so, because of course a model of a mug is like the model we activate as an example of such a model. We just need to distinguish between content and vehicle: the substrate is not like its content; neurons are not like mugs; experiences of blueness are not blue. This tension between misrepresenting our mental states by using them as examples of themselves will be a recurring theme when we consider phenomenal consciousness and qualia. To some extent, this conceptual drift between vehicle and content is unavoidable, and there is no harm done provided that we manage to avoid confusing ourselves. (In general, I propose, we do confuse ourselves, committing the phenomenological fallacy, but that’s a discussion for later.)

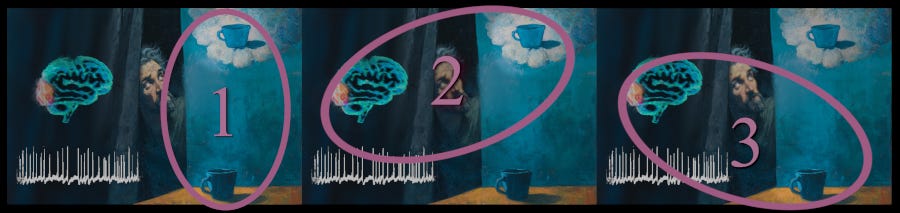

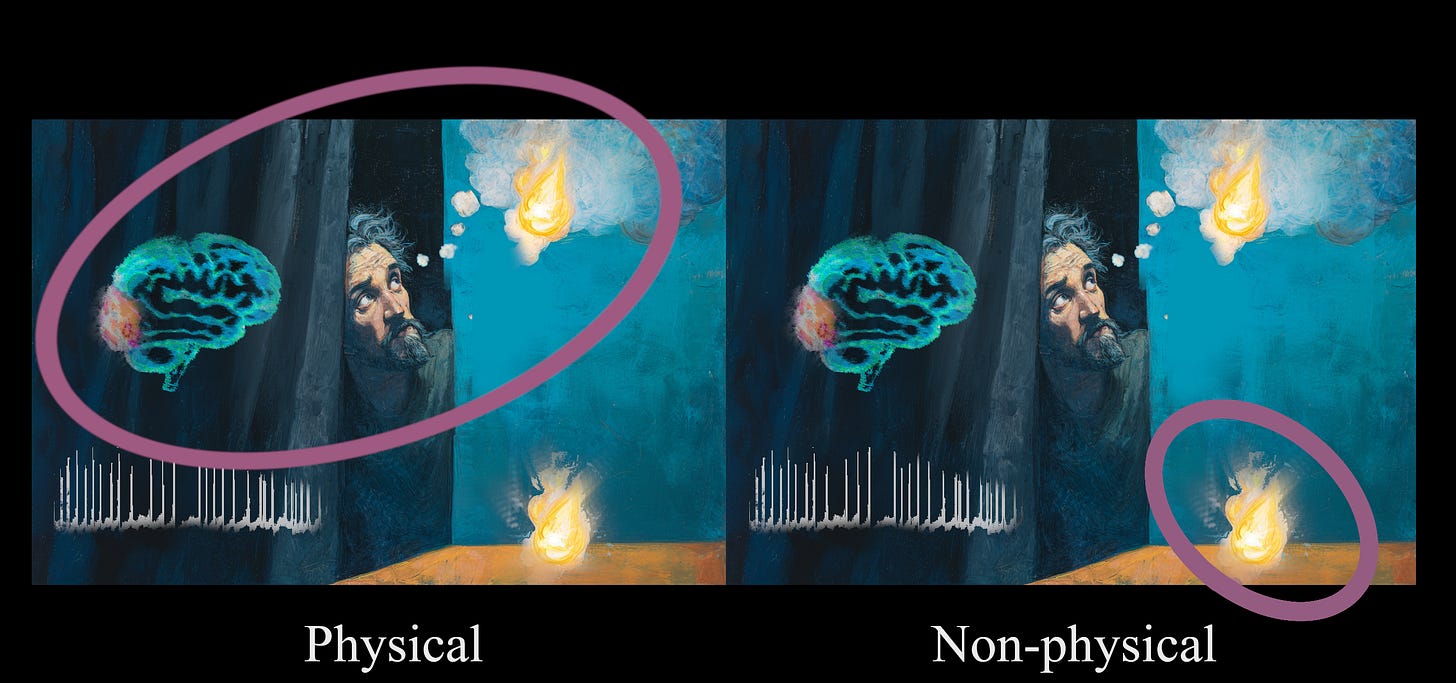

Note that the three elements under consideration produce three different conceptual pairings, illustrated in the figure below:

1) The neural model’s implicit content, which we might crudely think of as the “mind-mug”, shares with the ceramic mug the features of being the “intentional object” of the model, of seeming like a mug, of seeming blue, of seeming to have its ontological attachment to reality via a piece of ceramic on the table, and so on.

2) The neural substrate and the “mind-mug” share a single ontological footprint, within the brain of the perceiver. They are two views of the same actual entity. As such, their fate is inseparably linked, and they will be concurrently affected by any brain processes that make the coalescence between model and target go awry.

3) The neural substrate and the ceramic mug share the property of being straightforwardly real in a physicalist framework, without requiring any special pleading or ontological twists. They both belong in a first-pass list of genuine ontological ingredients.

Confusingly, the term “representation” can be used to describe the relationship within any of these three pairings, though it is most often used to describe the relationship between a neural substrate and its vindicating target (“3” in the figure). The important question of what things are like depends more on the substitutional convention that lets two things with the same ontological footprint be considered as vastly different (“2”); it is in this sense that I think representational views of consciousness are most useful, because science doesn’t have to account for how one side of this pairing “gives rise” to the other if they are actually the same ontological entity. On the other hand, the only reason the mind-mug has the properties it seems to have is that it stands in a distant causal relationship with the ceramic mug, so representational considerations account for the properties that seem to be shared between the two mugs (“1”), and the assumption of similar sharing for phenomenal representations is what gives rise to hardist belief in off-stage vindication of phenomenal content.

If we don’t draw these distinctions carefully, we can slide within and between pairings and get confused by the fact that the mind-mug has an intimate relationship with two different ontological entities: it is neural and it is also pseudo-ceramic, and yet we will nearly always treat it as genuinely ceramic by default. If we are careless, we can form the habit of thinking all of our representations are similarly vindicated.

The important point is that we only know about external reality through its neural representations, and, when the expected relationship between representation and reality is atypical or comes apart, it is especially important to understand that the two different types of “intentional object” are not the same, and not all intentional objects are ontologically vindicated. Imprecise terminology that is tolerable in the case of veridical representation becomes downright misleading in the case of “phenomenal consciousness,” leading the unwary to propose whole new domains of reality.

With these three entities identified, we can now acknowledge that the vindicating entity for a representation can be entirely absent, but representational considerations still apply.

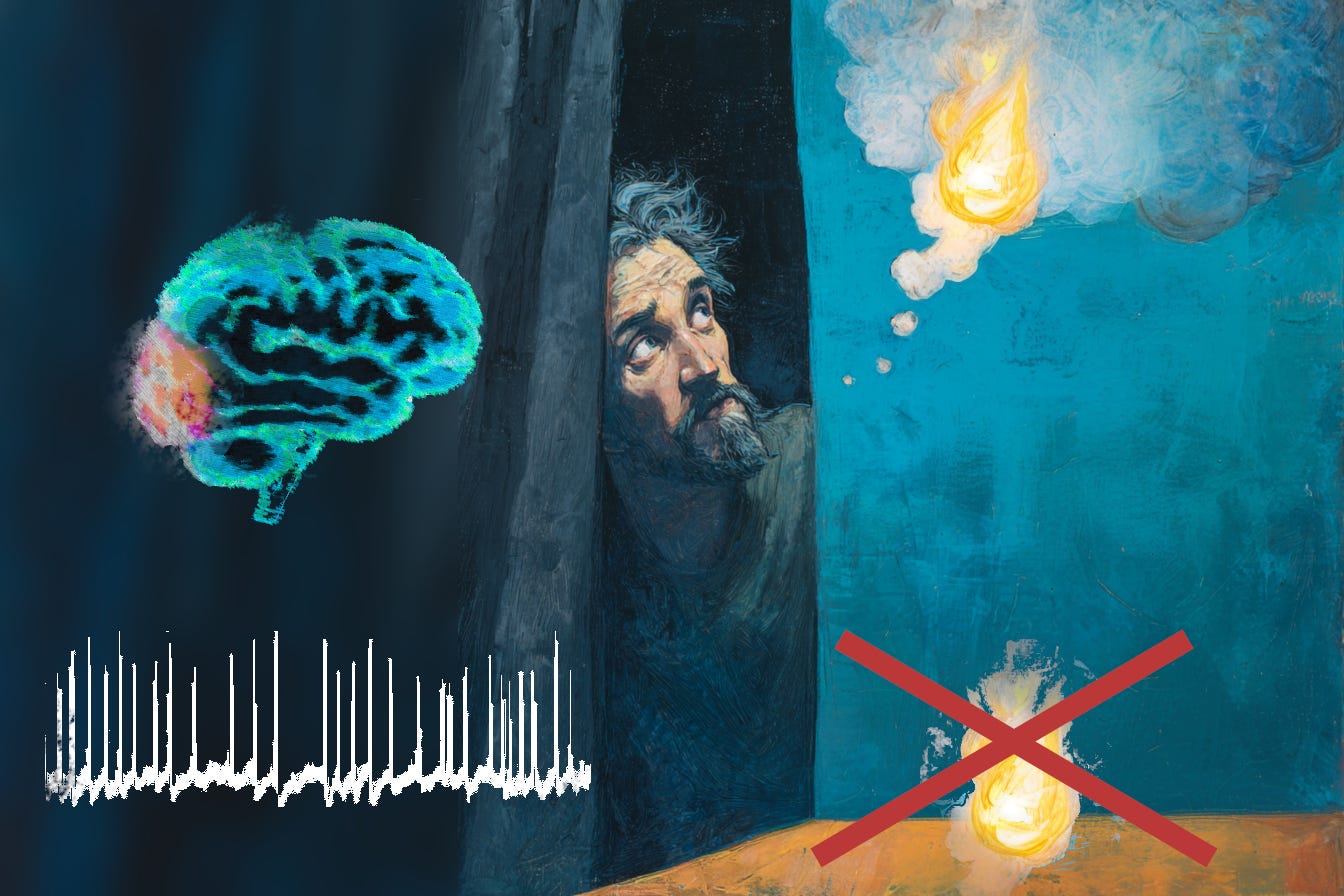

Consider the situation in which a curtain separates me from a real blue mug, and someone silently obliterates the real mug with powerful lasers, but I continue to think it is there beyond the curtain. In that setting, my mind‑mug would refer to an outright fiction: a neural representation of something that did not exist.

Following obliteration of the real ceramic mug, the mind‑mug would now be a fiction in two different ways that are easily conflated. It is worth pausing to consider the difference between these two different types of fiction, because we will eventually note the same two types of unreality with different versions of “phenomenal consciousness”, and both types of fiction will feature in debates about whether virtualism and illusionism are denying something undeniable.

Firstly, the mind‑mug is not a real mug, not even when it results from looking directly and soberly at a real mug under natural lighting, not even when it is causally upstream from linguistic output like, “That’s my mug!”. As already noted, the mind-mug is not constrained by the same sort of physics that usually applies to real mugs, and its physical substrate is not remotely mug‑shaped. To say that the mind‑mug is a fiction in this sense is not to imply that any mistakes have been made or that the cognitive system has suffered from an illusion; this is simply the result of a representational system doing its normal job correctly.

Secondly, if the ceramic mug is subsequently obliterated on the far side of an opaque curtain, the alleged “real” mug (targeted by the mind‑mug and erroneously believed to still be present) becomes fictional in an entirely new sense that is quite different to the way that the mind‑mug has been a mere representation all along. The “real” mug in this setting is now even less real than the mind-mug.

These two modes of being fictional reflect the two types of intentional object. All intentional objects, conceptualised in terms of implicit content, are not made of anything when things are working normally, because they are mere representations; some intentional objects, now conceptualised as vindicating targets, are not made of anything because they don’t exist.

The concept of dual fictional status is likely to be unfamiliar to most readers, so it might be helpful to note that, in the mundane case of the mug, these two different ways of being fictional derive their fictional status from different sides of the curtain. The mind‑mug is fictional in the sense that all mental representations are not real, because of factors that lie entirely on the brain side of the curtain – namely, the indirect representational relationship between the neural substrate and its content, and the associated hard‑wired convention of interpreting neural spikes as something else. Whether or not the alleged real mug is fictional in a second sense, making the mind‑mug a representation of a mug that is not really there, depends entirely on what has happened on the far side of the curtain.

Virtualism, recall, proposes that many of our mental representations consist of representations without a vindicating target. In that case, we can talk about all three of the notional entities in this conceptual schema, but one of them is entirely non-existent. Like the obliterated mug, the vindicating target for a Chalmersian conception of phenomenal consciousness does not have a tenuous or indirect relation to reality; it simply does not exist. Another form of phenomenal consciousness has a virtual existence; it exists as an interpretation of a model, and hence as a real high-level feature of that model, but it is a high-level feature that requires the adoption of a particular representational convention, so it can be ignored.

I propose that the zombie thought experiment splits this difference. Zombies are plausible because their creation involves removing the vindicating target that was not there anyway, and we can adopt a double standard in the face of complete duplication of our own cognitive apparatus because “phenomenal consciousness” is based on the implicit content of a neural model; it has an existence sufficiently ambiguous that we can consider it to be there when needed for the exercise and absent when not.

It is, perhaps, tempting to think that consciousness is a special case and that it is always veridical. Consciousness is just how things seem, says the hardist, and it makes no sense to say that things don’t seem the way they seem; illusions can never reach consciousness itself because consciousness is the basis of all seemings. A non-veridical representation of a mug that no longer exists might lack the physical vindication it seems to have, and a red-stripe after-image might not involve any photons of the corresponding wavelength, but there is at least some phenomenal domain in which those false images appear. We can mistrust what appears within that domain, but not the fact of their appearance. And that’s all consciousness is.

By analogy, a hardist could argue that a movie might depict a fictional dragon, but at least the screen is real, and on that screen there really is a dragon-shaped cluster of pixels. There really seems to be a dragon, and the seeming is real, even if the dragon is not.

This is, for some people, a tempting line of thought, and versions of this argument appear frequently in discussions of consciousness, but this is just what virtualism tries to clarify: the seeming is real, but the mere seeming comes with no ontological guarantees. To seem a certain way entails only a very thin claim on existence, with no assurances of how the seeming came about. Virtualism insists that the “real seeming” is only dependent on the neural models and their implicit content, and it is not due to anything playing out on an inner screen of consciousness that has its own separate ontological footprint.

In my experience, it can take many years to see the value of this perspective and to accept the mere possibility that the undeniable nature of consciousness might itself be misaligned with reality — that things behind the curtain are not necessarily as we think of them. For many readers, I’m sure, it is not yet even clear what it would mean for consciousness not to be what it seems to be, because they align their view of consciousness with the implicit content of their model, not realising that this is a specific definitional choice, and it means giving up on an alternate definition of consciousness as the vindicating target.

We can only approach these ideas with imperfect imagery, stuck within the system we are trying to question… But take the dragon movie of the hardist’s analogy, plug the video cable directly into your optic nerves in such a way that your visual system receives exactly the same inputs as it would have obtained from a real screen, and then the revised analogy starts to capture the virtualist view. The screen does not need to exist for the seeming to carry on. In this updated arrangement, the movie screen is now as fictional as the dragon, and once more we can apply our rule of threes. There are three dragon-like entities under consideration: the neural model in the movie watcher, the virtual dragon whose adventures are being followed, and the vindicating dragon that, if it existed, would make the neural model veridical and the dragon adventures non-fictional. The apparent visual milieu (the video screen that has been bypassed and is now merely virtual), shows a similar three-fold conceptual split, and the vindication is missing.

Virtualism extends this three-fold split to the mind of the watcher, while also insisting that, on the other side of the ontological curtain, there’s nothing there.

A central claim of virtualism is that a similar three-fold conceptual split can be applied to most aspects of phenomenality, even to the most obvious and seemingly undeniable aspects of our mental interiors – but when it comes to phenomenal entities, there is no sensory step, no translation from what is real to what is represented, and no calibration with the apparent targeted object, so inferring the vindicating entity requires an insecure epistemic leap of faith. So insecure that zombie philosophers make the leap and write books about what’s on the other side of the curtain.

Things really seem the way they seem, sure, but that does not mean they are the way they seem. The real seeming involves only one of the two types of intentional object, not the two types we met with our ceramic mug.

Under a virtualist framework, the mechanisms of consciousness give us our conceptual content on this side of the curtain; nothing needs to be sensed, and introspection is not sensation. Seeming to be a certain way does not require the presence of some real thing as a distal cause, so our usual extrapolation back out to the domain of the real leads us astray. Persuasive seeming can consist of de novo representations, pure intensional objects with no real-world vindication.

This is not the drastic demotion we sometimes imagine, because everything we think is real is similarly known to us via neural models, including straightforwardly real blue ceramic mugs.

Importantly, in arguing for a three-fold conceptual approach to phenomenal consciousness, I am proposing three conceptual entities per phenomenal property. If we want to distinguish between individual qualia, we would expand our taxonomy in sets of three. Three concepts to discuss phenomenal consciousness itself. Three concepts to discuss the redness quale. Three concepts for pain. Three concepts for the mild pain of a tongue burnt on coffee that was too hot. And so on.

Each of these three conceptual entities blurs at the edges, and the flavours themselves are not discrete, so this is at best an aid for understanding, not a rigid taxonomy.

If we lump consciousness and qualia together under the umbrella term, “phenomenal consciousness” (as hardists tend to do), we only need three concepts to capture a virtualist view of the major issues, so that’s what I’m going with for now. (We might decide that only two of those entities will, in turn, be sensible to believe in – but we still need to discuss the third one sensibly.)

If we decided to draw a distinction between consciousness itself and qualia (as I think we eventually should), we would end up with six important concepts: three for the phenomenality of consciousness, and a similar three for qualia. But we would have to say many of the same things twice over. The terminological issues I want to discuss are much the same for consciousness itself, viewed as a container (as in Baar’s global workspace or Graziano’s attention schema), and for the individual subjective flavours of perceptual content featuring within that container (qualia).

Qualia do add an important wrinkle to this three-fold conceptual split, though. If we wanted to include partial referents for qualia, like wavelengths in the case of colour qualia, we would need even more concepts. Some components of our perceptions would be vindicated, and some would not.

For instance, “redness” has a set of meanings that are independent of mental activity and therefore immune to most of the traditional qualia puzzles. There’s the objective “redness” of some reflective surfaces, and the different objective “redness” of photons or red light sources.

A tomato is red in a very different way than a red lamp is red, but we lump them together because both types of redness are known to us via photon streams. The tomato absorbs light, taking in everything that is not red, and the “red” photons were already there before they bounced off the tomato skin; the lamp produces light, bringing “red” photons into being.

These different forms of external redness can in turn be subdivided into purely objective characteristics of tomatoes and lamps – characteristics that are indifferent to human retinal pigments – and the more challenging pseudo-property of familiar redness that is utterly unlike invisible light, such as infra-red. The distinction between visible light and invisible light is biological; it depends on neural events that happen well after the reflecting or photon-emitting has already taken place. The potential ability to be seen as red by a human is a real property of a ripe tomato even if it has never been seen by a human eye, in the same way that being heavy enough to kill a human can be a real property of a rock on a planet never visited by humans.

In turn, we can talk about the biologically-mediated concept of redness-out-in-the-world in its naïve, pre-theoretical form, using the concept we’ve had since childhood, or we can insist on the more troublesome adult version that carries an explicit conceptual footnote to the effect that much of the apparent flavour is added in-bound from the retina and then interpreted as an inherent property of an object distant from the retina.

When we try to identify properties that genuinely reside outside the skull – asking, for instance, what it means to say that an unseen tomato is red – it is an awkward fact that some of the objective properties out there consist of the ability to produce potential reactions in human nervous systems.

Making the status of colour even more complicated, colours can be defined by ratios of photon frequencies rather than wavelengths… Light can be subjectively yellow without having any individual photons of the wavelength we would normally consider yellow, and some colours (like magenta) cannot be achieved with any single wavelength. Those ratios can be identified objectively, but our reasons for doing so reflect an interest in human perception more than the physics of light.

The objective existence of these various types of external colours can make it difficult to understand the hardist claim that colour qualia pose challenges to physicalism, or the virtualist counter-claim that an important aspect of subjective colour is merely virtual.

More generally, the properties of external objects can be described in terms of their local physical characteristics, without reference to how they are perceived by any biological entities, or they can be described in terms of their potential ability to produce reactions in organisms with various senses, and neither of these approaches will expose the explanatory challenge of qualia. These approaches will generally leave out the qualities that cause all the confusion.

In this post, I won’t be talking further about any of those external components that partially vindicate our perceptual representations, though they often get mixed up with each other and with our concepts of qualia in important and confusing ways. In the case of qualia, the hypothetical vindicating target for any qualia concept will end up being something of a compound entity, with some objective components that provide partial vindication for the concept (such as photon wavelengths or reflective properties) and some qualitative virtual components that defy verbal description and simple reductive analysis (the mysterious subjective quality of redness).

It’s easy to lose track of all this, so let me remind you of the three conceptual entities I do want to talk about: the neural substrate of a phenomenal concept, its implicit content, and a hypothetical vindicating target.

Somewhat confusingly, as we’ve already seen with Dennett, many philosophers focus on representation as being all about the intentional relationship between a model and its vindicating target, rather than as a way of making sense of implicit content. In the same vein, the term “intensional object” is ambiguous, and it can be interpreted narrowly as only meaning a vindicating target. If representational terms are defined in this narrow sense, and there is no vindicating target, it can seem as though the principles of representation have no relevance to the discussion. That’s unfortunate, because the chief difference between hardists and virtualists comes down to representational issues, and we need to understand all three aspects of the representational arrangement to see why.

If we started with these three conceptual entities, but then wanted to include the neural models of each of these three concepts, and have meta-concepts of each of those models, the number of concepts and entities would blow out somewhat – but not to six, for reasons you might already be able to guess. (When we extend the discussion to meta-concepts, we need a whole new concept to account for the neural model of the neural substrate, but we don’t need a new concept for our neural model of the implicit phenomenal property, because that was one of our original three entities anyway.) We will need some of these meta-concepts later, but we need to understand the basic three, first.

If we started worrying about the relativity of qualia, and questions like whether we have learned to like a taste or the taste itself has changed to become likable (a theme explored by Dennett in “Quining Qualia”, 1988), we will find that many of our concepts have indeterminate content. Let me concede, then, that much of the implicit content of the brain’s representations is irretrievably vague and only interpretable from the perspective of a cognitive system that blithely ignores the vagueness. That’s an important limitation on the three-fold approach I am proposing, but it is not fatal to the project of advancing understanding. Representational imprecision is all the more reason to suspect that vindication of our qualia concepts is impossible, but it’s not a reason to reject representational approaches completely.

If we brought zombies into the story (either directly or by approaching these issues as a strong hardist), that would necessarily mean we were introducing additional meta-concepts via duplication and having our notional twins do the same. We would find ourselves employing recursive concepts that threatened to spiral off into an infinite regress as we tried to put semantic distance between ourselves and our notional twins. (Spoiler: it isn’t possible to safeguard any human-specific definition of anything in this field; we can only ever use terms that zombies define identically for the same cognitive reasons, leaving us quibbling over whether our human words can ever manage to refer to anything extra that hypothetical zombie words fail to refer to.)

None of that dizzying proliferation of meta-concepts will be necessary at this stage.

For now, we can focus on just three concepts.

This is not the usual approach, but the need for three concepts is built in to the primary tenets of virtualism, and the nature of representation itself. Up above, I considered ambiguity in discussions of “intentional objects”, where Dennett ends up superficially conflating different meanings of the content of models. In other posts, I have considered ambiguities in the term “phenomenal consciousness” and argued that this can lead to empty debates between physicalists (See, for instance, “On a Confusion about Phenomenal Consciousness”.)

Even more importantly, the three-fold conceptual split that I want to address is there in the hardist literature anyway, in the form of competing dualisms, though it is not always explicitly acknowledged.

To see this, let’s consider traditional dualism.

What is now known as the Hard Problem of Consciousness is a descendent of the Mind‑Body Problem, which challenged scientists and philosophers to explain the relation between two apparent domains: the mental domain with its conscious mind, and the physical body with its neural mechanisms.

It is common for modern philosophers to trace this mind‑body dualism all the way back to the substance dualism of René Descartes, who gave the idea explicit expression in the seventeenth century (though the idea of a soul is even older). Descartes famously proposed that he had reached bedrock epistemic certainty when he introspected and found himself, a thinking entity. This insight was captured in the most famous line of philosophy: I think, therefore I am.

He subsequently argued that he could doubt the existence of the material world, but not the existence of himself as a thinking entity, and he took this as proof that the mind and the material world must be ontologically different. After all, they have different resistances to doubt. He convinced himself of the existence of two different types of substance: res cogitans (thinking stuff) and res extensa (physical stuff).

Many readers will recognise this as a fallacious ontological extrapolation from an epistemic situation: the differing resistance to doubt could reside in two different epistemic modes of access to a single entity. A more cautious interpretation of Descartes’ initial insight would have been that something existed, some medium capable of thought, and within that something he had two distinct concepts that he was unable to link with certainty, such that it was reasonable for him to doubt whether they ultimately applied to a common ontological entity.

Having proposed two domains, Descartes immediately encountered the central challenge of all dualist belief systems: somehow, he had to account for their relationship. Given that our minds are able to sense the physical world, and our physical bodies respond to our thoughts, Descartes posited a two-way causal interaction between the two domains, with one causal link running from body to mind and another causal link running back from mind to body, a framework we would now call interactionist dualism.

In this view, the mind is not a functionless epiphenomenon; it is right there in the middle of the causal story. Zombies under Descartes’ framing would not be possible.

Descartes then abandoned all pretence at epistemic caution and chose the pineal gland as the point of interaction, inspired by its central position in the brain.

From where we are now, this all looks rather silly, but most modern arguments in the philosophy of mind recycle similar themes. In the contemporary literature, Descartes’ interactionist dualism is usually rejected on the grounds that it would violate accepted laws of physics. Also, neuroscience as it is currently understood already seems adequate to account for behaviour. The brain has no receiving or transmitting stations that stand ready to interact with an invisible domain; it looks and acts like a closed system, apart from the obvious sensory inputs and motor outputs.

Given these issues with interactionist dualism, the current debate is often between non-interactionist dualists, who want to invoke two domains or two sets of properties to account for our intuitions, and two different varieties of monists, who think we can get away with just one domain.

Idealists are monists who argue that everything is actually mental and physical reality does not exist except as a construct within the mental domain. From where I stand, idealism still needs some aspect of the mental domain to comply with the laws of physics, to be the stuff that physicists study with extraordinary success, and to keep track of all the regularities that we would ordinarily call physical, so dualism is lurking beneath the surface of idealism anyway and nothing much has been solved. The Hard Problem and the Zombie’s Delusion are still in play, as much as idealists like to say otherwise. But that’s a debate for another day.

Physicalists like me argue that, despite some intuitions to the contrary, everything is ultimately physical, including consciousness.

Dualism lurks here, too.

Some physicalists are fundamentally sympathetic to strong hardism, with its claims of a mysterious rift between physical and mental properties. They might accept that everything is probably physical, but they nonetheless envisage weird physics or strange emergence stepping in to account for mentality in a way that is not directly entailed by the brain behaving in the ways described by contemporary neuroscience. Neuroscience textbooks are still missing some crucial element, and a future breakthrough will open up a new domain within the extended scope of a revised physicalism. These dualist-leaning physicalists essentially believe in whatever we would call ectoplasm – if only ectoplasm could be accommodated somewhere, somehow in a physical ontology.

Sometimes the ectoplasmic features are reduced to a subordinate property that lurks inside every element of the physical world, in a view known as panpsychism. It is somewhat arbitrary whether we file panpsychism under monism or dualism, but it is essentially dualist in flavour – atoms do what they do for physical reasons, and feelings tag along adding flavour. The usual problems with dualism remain. Again, that’s an argument for another day.

Other physicalists reject hardism, at least in its strongest form, arguing that we merely face a conceptual dualism, rather than an ontological dualism, and in general I agree with this sentiment. There are not two substances or two incompatible sets of properties, just two types of concepts in human brains, with epistemic difficulties arising when we try to connect them.

The case for such a framing has been clearly put by David Papineau.

[Quote]

Conscious properties are identical to material properties – that is, they are identical either to strictly physical properties, or to physically realized higher properties.

Still, while I am a materialist [physicalist] about conscious properties, I am a sort of dualist about the concepts we use to refer to these properties. I think that we have two quite different ways of thinking about conscious properties. Moreover, I think that it is crucially important for materialists to realize that conscious properties can be referred to in these two different ways. Materialists who do not acknowledge this – and there are some – will find themselves unable to answer some standard anti‑materialist challenges.

I shall call these two kinds of concepts `phenomenal' concepts and `material' concepts.

David Papineau, 2002, Thinking about Consciousness.

Papineau goes on to argue that phenomenal concepts are often of a quotational nature. We hold up an example of the concept when we want to refer to it. That quotational practice can be turned upon itself, so that our concept of a phenomenal concept naturally references itself at the same time that it references the property it is supposed to be about. We can think to ourselves, “A redness concept is like this”, and think of redness as an example of what it is like to think of redness. We are immediately at risk of what a linguist would call use-mention confusion. Are we using the representation of redness and thinking that a redness concept is red in some way? Or mentioning the concept, holding it up as an example, effectively disabling the meaning with unseen quotation marks? If we are not careful, we can easily think of mental states as having the properties they represent, as being red or painful, or lit from within by awareness. And science will not be able to explain how those states acquired properties that they don’t, in fact have, giving us a facile version of the Hard Problem.

I don’t agree with everything Papineau has written on consciousness, but I strongly agree with him on these issues. Like him, I think that most of the fuss in philosophy of the mind arises from what he calls conceptual dualism, which creates a strong intuition of distinctness between the material and phenomenal approaches to mentality; this intuition paves the path to belief in ontological dualism.

Whether this intuition of distinctness is a natural part of the human condition or simply a conceptual hazard for people who wander into hardist thought experiments is somewhat unclear, but I’m one of those for whom this intuition seems natural.

In a minor departure from Papineau’s framing, I propose that we need a minimum of three concepts to find our way out of this maze, not two: the neural substrate, its implicit content, and a hypothetical vindicating target.

That is, we face a conceptual triplism – or we should, if we want to watch the debate from above and understand both sides.

There are two different ways we can reach this conclusion: 1) by noting that we are dealing with competing dualisms, or 2) by applying a three-way conceptual split to consciousness viewed as a representation. That these two approaches converge is, perhaps, a clue that we are on the right track.

The logic of competing dualisms is simple. Papineau’s conceptual dualism fits entirely within the physical domain, and essentially consists of two different perspectives on a single brain-state, so if we add ontological dualism on top of his conceptual dualism, we need three concepts to talk about the full picture: two referring to a split perspective on the physical side, and one referring to a baffling non-physical entity on the mental side.

We get a very similar result if we approach the issues from a representational standpoint. If consciousness is a representation without a corresponding vindication in the physical world, then we would expect two perspectives in the physical domain, one for vehicle and one for content, and if we wanted to insist that introspection must be veridical after all, despite not finding its target in the physical world, we would need to invent a second ontological domain to host the vindicating entity.

Virtualism proposes that the three concepts necessary to keep track of the two dualisms correspond with the three notional entities we identified earlier, when we considered the possibility that the implicit content and the vindicating target of a model might not coalesce.

The concepts in the physical brain often purport to target the mental domain, and Papineau’s material concepts are about the substrate of his phenomenal concepts, so it can all get very confusing. But the confusion is there anyway, and I believe we have no choice but to name the elements within this complex situation.

And, as noted earlier in the discussion of two mugs, there are two different ways we might propose that an intentional object is not made of anything, and it is important for us to discuss those two different ways that “phenomenal consciousness” might be considered less than real — because one type of non-reality is nuanced and qualified, and can be shoe-horned into a recognition that phenomenal consciousness is sort-of-real after all, whereas the other type of non-reality is absolute.

The terms we choose to pin down these ideas are less important than the ideas themselves. In the following posts, I’ll use Latin for these concepts to fix their technical meaning, and to avoid the natural conceptual slippage that usually applies to regular English words (and to many of the standard philosophical terms in this field, such as “qualia”).

The substratum – the neural substrate for a phenomenal concept

The ostensum – the implicit content of a phenomenal concept

The externum – the vindicating entity for a phenomenal concept

Virtualism is a subspecies of physicalism, so the ontological backing for this proposed three-pronged approach is still entirely monist. That means, for any type of phenomenality (consciousness itself, redness, pain, and so on), only one of those three concepts will have a straightforward ontological instantiation within virtualism, and the other two are add-ons of a potentially dubious status. I propose that our modern scientific concept of the physical substrate of phenomenality is the clear ontological winner, and it is straightforwardly vindicated; atoms and neurons are real, and although we might be mis-imagining them or mis-describing them in some way, because physics and neuroscience are both ongoing scientific projects, we are essentially on the right track.

After we identify the neurons responsible for phenomenality, physicalism requires that we already have all the ontological ingredients before us, and we can only extend our conceptual reach by considering higher-order properties and functional relationships between those ingredients. This might not seem to leave much room for new conceptual entities within physicalism, and indeed dualists will insist that most of the important aspects of mentality been left out of the physicalist account. Consciousness itself, redness, pain, and so on, do not seem to be an inevitable part of the physical story of the neural substrate.

Personally, I’m happy to agree that this is how things can seem to some people; after all, that’s how things seem to me. I know some physicalists who say that this is not how things seem to them, and sometimes it can be difficult to know what to make of this claim – in part, because language lets us down, and all “seeming” is theory laden. Even if we do not all share the pull to dualism, though, we all need some way of talking about the concepts within dualist minds (and in the minds of some sympathetic physicalists).

In the next post, I will apply these terms to some of the classic hardist thought experiments. My diagnosis in each case will be the same: the substratum is real, the ostensum is virtual, and the externum is a hardist fiction that we would be better to abandon.

Postscript

To tie different threads of this blog together, note that the “externum”, when applied to so-called phenomenal consciousness, is just another name for spice; the substratum and ostensum are two views of the same thing, and constitute ostensional consciousness. For more detail, see On a Confusion about Phenomenal Consciousness.

Also, these three entities correlate with the three rooms of the likoscope lab in A Blue Square, Part 2 of the Likoscope Lab series that began with A Red Triangle.

Greatly enjoyed the article. Just for fun, not that I think I'm right or you're wrong, here is a criticism of the second level of triplism. I know you are aware of this criticism as you reference it multiple times in the piece (how the other two are "belong in a first-pass list of genuine ontological ingredients", implying the second is a bit shakier, and one other place too.) But I want to push you on it.

So let's talk about "implicit content", "meaning", "model", "representation", etc. These form a cluster of words that are all related and are important to many physicalist conceptions of the mind-body problem. But what are these things?

Here is a eliminativist-friendly definition. Suppose X and Y are real things that actually exist. Then X represents Y to the extent that there are structural similarities between them. These structural similarities could be the internal structure of X and Y, or they could be how X and Y fit into a larger environment. For example, the symbols "{{ab}, {bc}, {ac}}" written on a page and a triangle drawn on the page have similar internal structures, so these could represent each other. The word "car" written on a page and an actual car don't have any internal structure in common, but they play a similar roles: the word "car" often appears together with the word "driving" in a sentence, and a real car is something I could actually drive.

Okay, but what does similar mean? Humans are really good at abstracting in this way and thus would be good judges of similar, but of course if we're trying to understand human consciousness appealing to humans isn't too helpful. Another option is to use physical interaction as a guide. Stonehenge is a good example: it provides a sort of representation for the movement of heavenly bodies by how the light from the sun is in physical coincidence with boundaries of the stone structure. I think you could say Stonehenge is meaningful apart from any humans because of that physical connection between the stone and the heavenly bodies given by light. Similarly, I think one can say the brain represents the real world because of the sensory inputs and motor outputs that connect the brain and the real world -- you do a great job of going into more detail in your article. Suppose in an otherwise empty universe a square, a triangle, and the symbols "{{ab}, {bc}, {ac}}" magically appear. There is no special connection between the symbols and the triangle, because there is no physical coincidence aligning their internal structure, and there is no one to judge similarity.

Critically, nothing outside of physics appears in this definition: the brain, real world, sensory inputs and motor outputs all uncontroversially physical. So what is this mind mug you're talking about? What is the second level of triplism? What are Papineau's "physically realized higher properties"? True, there can be neurons that play a similar role in a brain as a car does in the real world, but it's still just neurons in there. Consider the case of a simple universe with no consciousness where the fundamental particles tend to form equilateral triangles. They don't actually form equilateral triangles: they just exists in the locations that they are. The idea that they form equilateral triangles is an idea in my head as a conscious human, not something that exists in that universe. To specify otherwise would to suggest mathematical entities are real and exist outside of various universes.

Now to be clear, I believe in a much richer picture than what I'm painting here. I believe the points do form equilateral triangles, I believe "{{ab}, {bc}, {ac}}" and an triangle have shared representational content even with no one around to judge, and I believe in the second level and implicit content. Indeed, I believe in just about everything that one could believe in. The point is that in order to take even the tiniest baby step from eliminativism to something richer, you have to grant the existence of something that is outside of the raw physical ontology.

You might say "A building is made out of bricks. The building is conceptually something more and distinct from the bricks, but ontologically it's still just bricks". But then you've used the word "conceptually", which is another one of these words like "models", "meaning", "higher-level properties", etc. Either these words are talking about a thing or they are not talking about anything. If they are not talking about anything, then we accept eliminativism. If they are talking about something, then we're already in dualism. And if we're in dualism already, why not accept redness as a real thing?

Lots here to respond to, thanks for all the work you've put into this. For now just a couple things from my phenomenal realist perspective and some links to relevant papers.

Re Dennett's afterimage of a red stripe: the represented red involved in the afterimage is no less real than that the represented red of an apple you see in front of you. Both are phenomenal (qualitative) contents with a corresponding neural substrate - the representational vehicle. The apple is spatially located but not the red in terms of which it appears, hence, as you put it, the red is virtual, or as I'd put it, part of your *representational* reality, as contrasted with what it represents - *represented* reality. I agree that "we only know about external reality through its neural representations...everything we think is real is similarly known to us via neural models." So the physical (external) appears in terms of the virtual - the content of the neural model. I've critiqued Dennett's red stripe at https://www.naturalism.org/philosophy/consciousness/dennett-and-the-reality-of-red

I agree that "Virtualism insists that the 'real seeming' is only dependent on the neural models and their implicit content, and it is not due to anything playing out on an inner screen of consciousness..." There is no such screen, but if we construe phenomenality as (real) content carried by the neural vehicles, then talk about phenomenality has what you call a vindicating target: a real, existing intentional object - the content. This contrasts with talk about unicorns which, since they don't exist, are the *non-existent* intentional objects of such talk. I explore this contrast at https://www.naturalism.org/philosophy/consciousness/why-qualia-arent-like-unicorns-a-defense-of-phenomenal-realism

I've got a 2019 JCS paper on this stuff at https://naturalism.org/sites/naturalism.org/files/Locating%20Consciousness_0.pdf and a more recent preprint along the same lines at https://psyarxiv.com/79xg8

Looking forward to more on virtualism...