Memory Systems

Visualisation and the Major Phonetic System

I have a serious post lined up, but while I wait to proofread it, I thought I’d drop a lighter post that is only tangentially related to my interest in consciousness.

When I was in early primary school, my father taught me how to memorise arbitrary data, like lists, numbers and packs of cards, using visualisation. The necessary techniques take some effort to master, but not much, and I was fairly proficient at it by age 9. I used it to memorise packs of cards in sequence, just as a proof-of-principle — a skill that came in handy when playing cards. Over a day or two, I also memorised pi to 300 decimal places, but I saw no point in going further at the time. After all, the universe isn’t big enough to contain a circle needing that accuracy.

Later, on a bush walk, my son and I learned 1000 digits.

The system was useful in school. The interesting aspects of school education don’t require much memorisation, but wherever school did require brute memorisation - dates, the periodic table, numerical values of any sort, foreign language vocabulary — I used the techniques. It made that part of school trivially easy.

When I did medicine, which was largely a matter of memory work, the techniques proved invaluable. Most of the crammed medical facts have since been replaced with a more robust familiarity with the reality behind the data, but some of the mnemonics have stuck.

Pisotifen is used for migraine? My friends and I memorised this as “Piss off Tiffany, I’ve got a headache.”

The match between the mnemonic and the data doesn’t have to be close; it only has to be good enough.

There are two basic components to the system: linking objects or actions with creative visualisation, and converting boring, bland information into more phenomenologically salient information. The idea, I guess, is to take advantage of our natural tendency to remember vivid events — to recruit our episodic memory and to flag the material as novel. If we remember a vivid scene that has a second meaning, we can sneak boring data into medium term memory, data that our brains would normally dismiss as not really worth the storage space.

But first we have to make sure the data is memorable.

Almost any data can be subjected to a transformation that lets it be visualised, but digits are the most frequently encountered example of boring data with poor natural potential for visualisation.

Luckily, there are roughly ten basic consonant sounds in human language — perhaps this is truer of English than many other languages, but there are workarounds for any language — so we can do a mapping of digits to consonant sounds. This is known as the Major Phonetic System.

0 = s, z, soft c

1 = t, d

2 = n

3 = m

4 = r

5 = l

6 = j, ch, soft g

7 = hard c, k, hard g

8 = f, v

9 = p, b

I’ll never learn that mapping, you say?

Well, we can go meta, and apply memory systems to memory systems.

Zero starts with a “Z” sound, and we always include similar sounding consonants: the “s” of “soup”, the double-s of “chess”, the “c” of “ice”. Consonants that only differ in whether they are voiced (“s” and “z”) are always given the same digit.

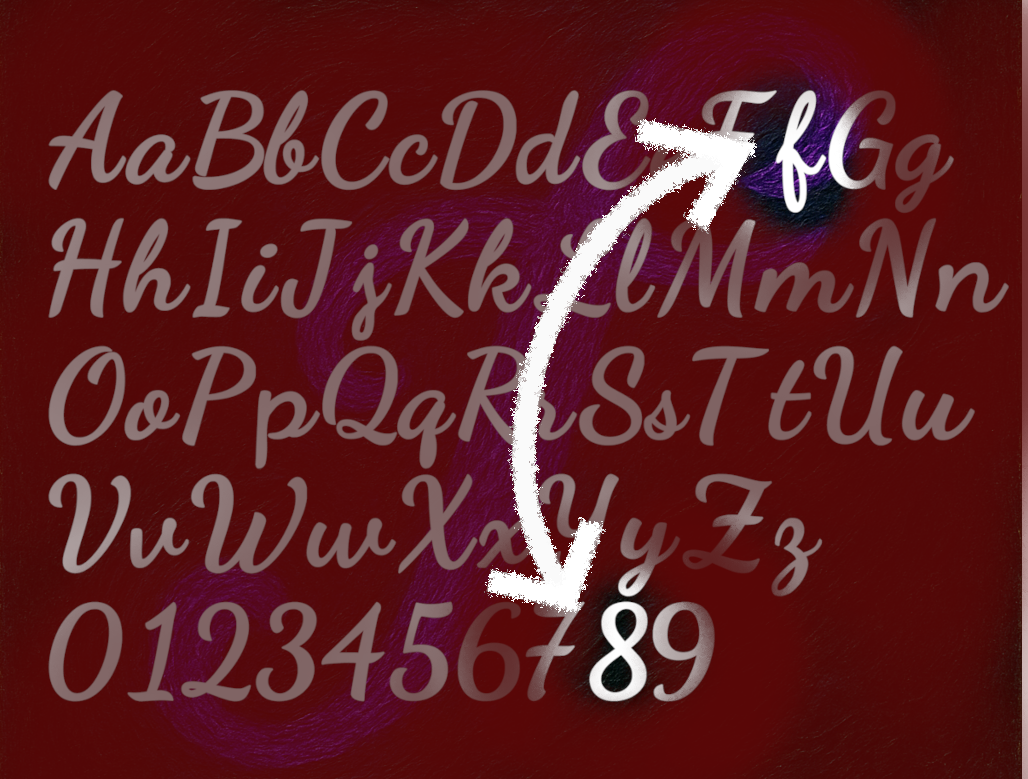

Here is an image to help you remember that “1” and “t”, both share a single vertical line, and therefore look similar:

To remember that “2'“ is “n” and “3” is “m”, note the two verticals of “n” and the three verticals of “m”.

To remember that fouR is “R”, just focus on the fouRth letter of fouR.

The sound for 5 is “L”, which is the roman numeral for 50. Close enough.

To me, 6 looks a bit like a “G”, or, in some fonts, two sixes can combine to make a “g”.

Similarly, two “7”s can make a “K”.

An old-fashioned loopy cursive “f” can look like an “8”.

A “p” and a “b” are both like a “9”, given the right flips and turns.

If you learn these mappings (and it doesn’t take long), every word has a unique translation to a string of digits.

We ignore vowels, and we disregard some of the softer consonants like “w”, “h” and “y”, which spell “why”. (“Will you aim low?” becomes “535”, with less digits than words, because we ignore so much).

Note that we base the mapping on how things sound, not on how they are spelled. “Pseudonumerology” becomes 0123456, because the “P” is ignored. You can use the word to help you remember the first 7 digits of the system. What could you use to cover the next three? I give up.

“Pseudonumerology? I give up.” 0123456? 789

There are a couple of corner cases, though. The sound “tch” from “witch” and “dge” from “judge” are usually treated like “j”, ignoring the barely pronounced “t” and “d”. We always do this if the 1-sound (“t” or “d”) combines with the 6-sound to form a natural grouping within a single word; conversely, the “t” or “d” is recognised if it comes from a different source word. That means “witch” is just “6” but “shitshow” is “616”.

Another convention I follow is that the “ng” of “sing” is treated as “27”, even though it is a single consonant. Some people treat this special consonant as a “2”, with no “7”. I don’t like this approach, because sometimes the “g” is audible, as in “bingo”, and sometimes it isn’t, as in “bang”, and sometimes it depends on one’s accent.

The letter “X” is “70”, because “bocks” and “box” sound the same..

Although each word has a unique mapping (given a fixed pronunciation), there are many possible mappings from any string of digits to a strings of words, which leads to flexibility in coming up with mnemonics.

When doing the digit-to-word conversion, it’s important not to try to be too clever. The easiest approach to memorising a number is to break it into groups of two or three digits, but sometimes a longer word saves time.

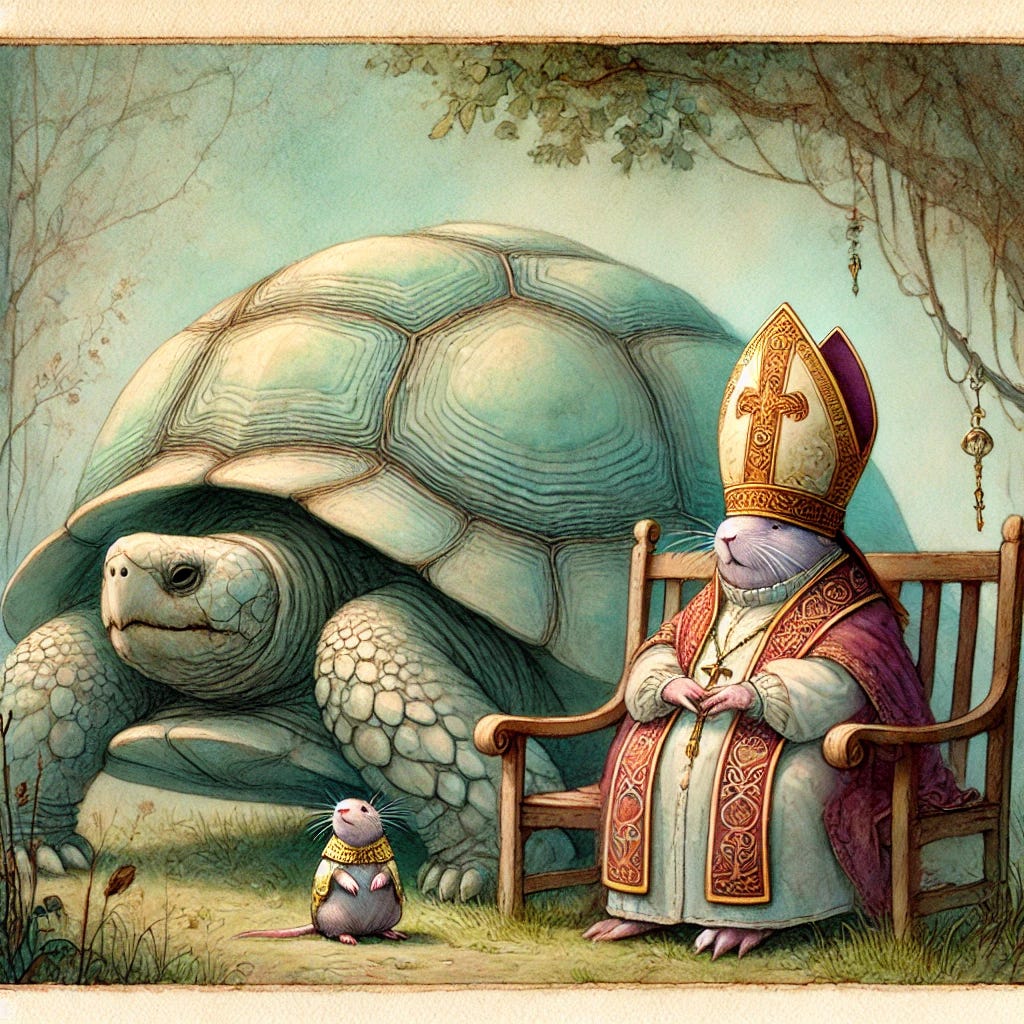

The first ten digits of pi, 1415926535, could be broken down in many different ways, but the first four digits make “turtle”, and the next three make “bench”. If we add a “holy mole” (which might be a hairy critter in priestly garb), we just have three images to combine. Picture a turtle sitting an a bench, being pestered by a holy mole. If it isn’t memorable enough the first time round, make them fight, have one of them draw blood, give one of them a ridiculous accent, or bright clothes, or whatever. Give them opposing ideologies. If you don’t remember the image, do the scene over. It’s always the director’s fault.

The technique gets easier with practice.

I’ll post more on this later, with a few tips on how to apply the techniques, but here are the first 250 digits of pi, 10 digits per line, 50 per verse.

Naked in a Steep Ice Pit

Lyrics by human, song by AI.

Turtle bench holy mole.

Heavy backup, moon-home, fridge.

Injury, mummy, foaming, bee.

Lesson of fire, 1971.

Cheap ham, baby, McLeods.

1415926535

8979323846

2643383279

5028841971

6939937510

Elphin speaker, prairie.

Loopy gnomes, cave teacher.

Sash knife, chain safe, baby.

Fashion face, more vinyl.

Maroon toad. Kiss cheek, happy!

5820974944

5923078164

0628620899

8628034825

3421170679

Fun dwarves, official tie.

Mean venomous witch shark.

Spam for "urges pill".

Less love, Nina, I'm taken.

Will you aim low? A press of the knife.

8214808651

3282306647

0938446095

5058223172

5359408128

Roof out the hot cruel sun.

Fred sang a sad poem.

Feline dudes, la-la-la, hippy.

Share a ration, now, brave hippy.

Will your poems move the beach?

4811174502

8410270193

8521105559

6446229489

5493038196

Rare in view of the speckle.

A judge will buy Mummy rare jade.

No frog will share venom.

My café shack, famed jelly.

Naked in a steep ice pit.

4428810975

6659334461

2847564823

3786783165

2712019091

First 250 digits of pi.

3.

1415926535

8979323846

2643383279

5028841971

6939937510

5820974944

5923078164

0628620899

8628034825

3421170679

8214808651

3282306647

0938446095

5058223172

5359408128

4811174502

8410270193

8521105559

6446229489

5493038196

4428810975

6659334461

2847564823

3786783165

2712019091

Great fun. My life’s goal is now to get “Naked in a Steep Ice Pit” trending on Spotify!

Very impressive! If you got to 1000 digits, that means you hit the point with all the nines in a row! I call it Hofstadter's point, although apparently it's better known as Feynman's point (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_nines_in_pi).